A summary of Russell Campbell’s book Marked Women: Prostitute and Prostitution in the Cinema (2006): The 14 female sex worker archetypes

Article by Hanh T. L. Nguyen

Abstract: This essay summarizes Russell Campbell’s book Marked Women: Prostitute and Prostitution in the Cinema (2006). The premise of Campbell’s arguments about the different kinds of representation of the female prostitute in film is that the global film industry has been dominated by men, and thus, prostitute characters in film are products of the male imagination (and for the male spectator). Although, of course, these characters are portrayed by female actors, they are written by men and the performances are directed also by men. This essay is a summary of the fourteen archetypes of the female prostitute character in cinema.

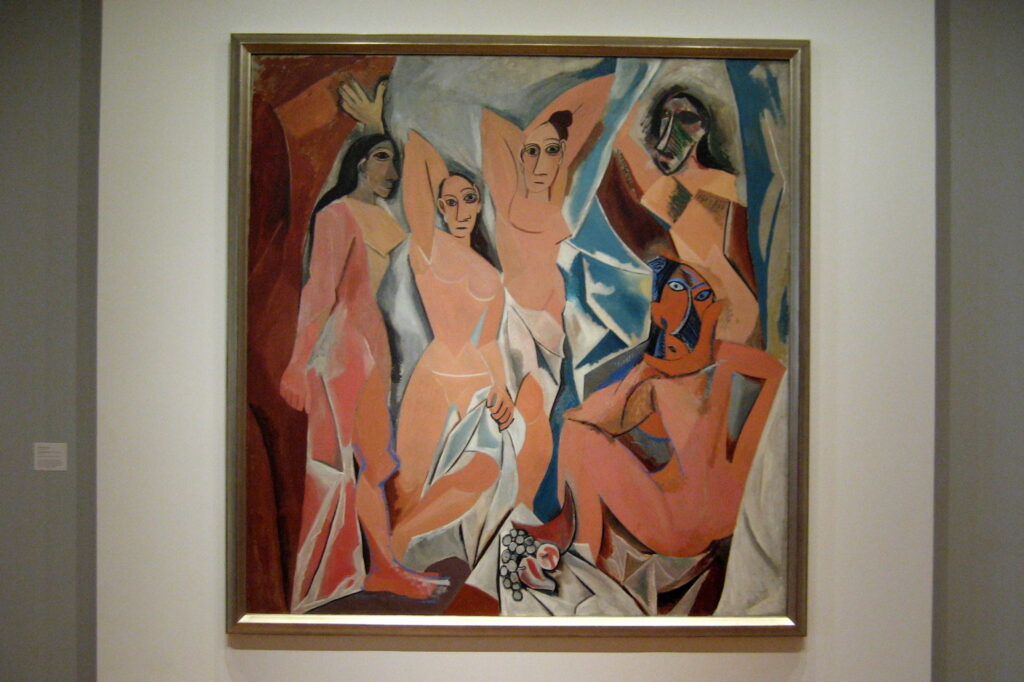

Header image “NYC – MoMA: Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” by Wally Gobetz is licensed under CC BY 2.0 DEED.

Introduction

Men have ambivalent and contradictory feelings towards the other sexual, including intense desires and anxieties, for which they find expression in the prostitute figure. She embodies both positives and negatives. In Campbell’s words, as “[a] symbol of eroticism in a sexually repressive society, or of endurance in the face of intense humiliation and suffering, she attains a positive coloring; but as a symbol of flesh against the spirit, of the polluted against the pure, of the commercial against the freely offered… she is negative” (p. 5). Because of this ambivalence towards the prostitute, she, in men’s imaginaries, represents many character types.

The following is a listing of Campbell’s fourteen cinematic representations of the female prostitute who is, to various degrees, both wonderfully alluring and extremely disquieting to the male mind. She represents both of what the male longs for and what he fears and deplores the most.

Archetype one: The Gigolette

The Gigolette is usually a secondary character, sometimes just a background presence, whose main “task” is to raise the erotic temperature of the film. She was more prevalent on screen before the sexual freedom movements of the 1960s in the West. She may be the love object for the male protagonist and because of her transgression of restraints on sexual behaviors typical of her time, she suffuses the film with a “rosy glow” (p. 41), such as Marie in Casque d’Or (Jacques Becker, 1952). As premarital and extramarital sex became much less the exclusive province of the prostitute, the Gigolette began to lose some of her power as a symbol of erotic liberation, except in period films.

Archetype two: The Siren

Like the Greek mythical creature whose mesmeric singing allures men to their demise, the Siren is a prostitute whose fickle, flirtatious nature is responsible for wreaking havoc on a man’s affairs, be they business, familial relationships, or his state of being a conscientious, law-abiding citizen. However, despite her destructive impact on the lives of her admirers, little moral opprobrium is directed at the Siren since a back story of her fall, which invokes the audience’s sympathy, is usually provided, unlike the Gold Digger archetype, whose insatiable desire for material things induces her to be a selfish, unsympathetic woman and thus, contemptible.

Archetype three: The Comrade

The Comrade epitomizes socialist viewpoint of prostitution, which is the oppression of women and one of the evils of capitalism. The Comrade rises against a society that has relegated her to the bottom of the heap, and in so doing, she becomes a positive figure in the fight for justice and liberty. Her polar counterpart on the broad field of left-winged politics (i.e., from socialism to anarchism) is the Business Woman archetype who very likely embodies the very characteristics that are condemned by socialism. An example of the Comrade film is Xiao Fengxian/The Little Phoenix (Kuang-Chi Tu & Hsin-Po Hsu, 1953).

The Comrade is portrayed as a locus of virtue in a vicious world that only delivers misery. She is either innocent, or if compromised, then it is made obvious that she is not as corrupt as the men with power around her, like Nguyệt (Minh Châu) in Cô Gái Trên Sông/Girl on the River (Đặng Nhật Minh, 1987) whose corruption in prostitution is nothing compared to the ungratefulness and hypocrisy of official Thu (Anh Dũng). The Comrade is fortified through hardship, which gives her a political consciousness, an awareness of exploitation, oppression, and social injustice. The Comrade calls attention to the scrupulous nature of capitalist society, brings to light the hypocrisies of the bourgeoisie, and embodies the virtues of solidarity and comradeship in a proletarian milieu.

Archetype four: The Avenger

The Avenger is a prostitute who, being sexually exploited, fights back against the conditions of her oppression, or the oppression suffered more generally by women in a male-dominated, sexist society, especially in the prostitution business. In a common scenario, she takes revenge on the person who is responsible for her wretched condition, such as a rapist, a sexual abuser, or a violent pimp. Most provocatively, from a male perspective, she may wreak vengeance on men who are not necessarily personally guilty for the violence inflicted on female victims, but standing in for the actual perpetrator, since all men profit from a system of gender inequity. An example of the Avenger film is Satyajit Ray’s Ashani Sanket/Distant Thunder (1973), in which Chutki (Sandhya Roy) is forced into prostitution in exchange for rice and later beats a man who had sexually assaulted another woman to death.

Archetype five: The Martyr

Doubtlessly, the Martyr archetype in Western cinema is heavily Christian, specifically Catholic, in origin. In Martyr films, it is the prostitute’s destiny to suffer from, for example, violence from her pimp or client, imprisonment, or (terminal) illness as a result of being a prostitute (such as venereal disease). Otherwise, the scenario of growing old as a prostitute with no prospect of a different, better life may be tormenting enough, as explored in Bruno Rahn’s Dirnentragödie/Tragedy of the Street (1927) or, more recently, Lee E-yong’s The Bacchus Lady (2016).

“working_2006” by andronicusmax is licensed under CC BY 2.0 DEED.

Archetype six: The Gold Digger

The Gold Digger is a product of male imagination resulting from men’s anxieties and insecurities about women’s sexual independence. The Gold Digger is the most negative archetype of the female prostitute who is morally corrupt beyond redemption, and thus is an object of misogynist contempt. She is often portrayed, variously, as untrustworthy, dishonest, heartless, treacherous, and incapable of fidelity. She loves money and material things above all and has little sympathy for others. An example of the Gold Digger archetype is Ginger (Sharon Stone), in Casino (Martin Scorsese, 1995).

Archetype seven: The Nursemaid

The Nursemaid, a nurturing prostitute for a boy or man, is an archetype that is deeply entrenched in male fantasy fulfillment. If quick sexual gratification is what most clients get from a prostitute, it is not necessarily what they want the most. Rather, they long to soothe loneliness, want a contact that is both physical and spiritual, a kind of love that is most likely missing in their lives. The Nursemaid is created to offer this love, that is, “an understanding and nurturance miraculously combined with an erotic allure” (p. 168).

In creating the Nursemaid, the impossible Oedipal dream fusion of lover and mother, male filmmakers indulge a taboo fantasy. The Nursemaid could also nurse inspiration and be a muse for the artist, like Sera (Elizabeth Shue) for Ben Sanderson (Nicolas Cage) in Leaving Las Vegas (Mike Figgis, 1995). In Campbell’s words (p. 174), the Nursemaid “recites the script that the client has written,” which means that she provides for whatever desires men have for a woman/mother/lover.

Archetype eight: The Captive

The Captive is the woman who is trapped in her situation as a prostitute under the heel of the pimp, brothel owner, or criminal organization she works for. Unlike the typical fallen woman whose sexual experience and loss of chastity are to blame, Captive films’ criticism is directed towards the fact that she is coerced to sell her body and exploited in the process. The woman is often deceived and forced into prostitution with violence or drugs.

There are two motivating forces behind the reoccurrence of the Captive films. The first motivation is the outrage at the stubborn social reality of enslavement and exploitation of women in forced prostitution. The other motivation, quite different in nature but coalescing very well with the first one, is the strong male fantasy of the sex slave, the beautiful sexual other who may be stripped, chained, and raped unreservedly. The Captive figure provides an opportunity for the portrayal of sexual activity and violence, especially against women and enables filmmakers to dwell in visual eroticism, often sadomasochist.

Archetype nine: The Business Woman

The Business Woman engages in prostitution without any guilt, or qualms, regarding its morality. She considers herself an entrepreneur and is in charge of her own affairs, so she does not suffer like the Captive or Martyr. She may expand her business interests and become a madam. The ultimate variant of the type is the dominatrix, who holds power over masochist men.

Depending on the filmmaker’s political standing, there are two polar opposite ways to deploy the archetype of the Business Woman in film. For critics of capitalism, prostitution is a symbol of the distortion of interpersonal relationships and the human alienation that occurs in a society where all activities become commercialized. Deploring prostitution, anti-capitalist films usually approach the Business Woman satirically. They often portray a lack of human fulfillment, an absence of deep connections, self-objectification, and a relinquishment of individuality to mass consumerism.

For advocates of free enterprise, on the other hand, prostitution can serve as an illustration of the idea that the market economy enables the fulfillment of human desire in all of its diversity and deviations. Business Woman films can be recruited as a means to communicate the sex radical idea that prostitution too can become an occupation just like any other. These films stress the entrepreneurial aspect of prostitution, the necessity of preventing pimps from exploiting sex workers, and prostitute women’s mind for business. Many films of the Business Woman archetype feature the catering of kinky tastes and outré sexual practices. Apart from the comedic value, this trope highlights the diversity of human desire, which only a commercial sex industry can accommodate. These films portray opponents of prostitution as narrow-minded hypocrites, for example, corrupt police who can always be bribed with sex.

Archetype ten: The Happy Hooker

The Happy Hooker character, like many other archetypes proposed by Campbell, provides a valuable opportunity for men’s carnal pleasures to be satisfied in film. The films, represented by The Happy Hooker (Nicholas Sgarro,1975), depict women engaging in sex work voluntarily and with high satisfaction, thus openly endorse prostitution and propose, by implication, that society be honest and less hypocritical towards it. The Happy Hooker films reject the socially accepted assumption of the fallen woman scenario: that women enter prostitution through having been mistreated by men.

The Happy Hooker is usually portrayed as a prostitute with a voracious sexual appetite, which allows patriarchal filmmakers to depict prostitution as a blameless institution since the women involved rejoice in it. If the sex worker is a nymphomaniac who revels in sex work, any patriarchal guilt about prostitution can be assuaged.

However, the Happy Hooker can cause intense anxieties in the patriarchal mind because she is a woman who initiates and enjoys sex and who turns sexuality to her financial advantage. She eludes male control and achieves individual autonomy, agency, and subjectivity. The ending of many Happy Hooker films seems to suggest that the indulgence in erotic fantasies with prostitutes has to stop at some point, as in The Best House in London (Philip Saville, 1969).

Archetype eleven: The Adventuress

The Adventuress is one of the few archetypes in the male imagination that concentrate on the subjective experience of the prostitute. She uses prostitution to run away from the tedium and dissatisfaction that she has to endure in her relationship with her male partner, to discover her own psyche, and to fulfill her sexual desires and fantasies, often in secret.

The Adventuress challenges a bourgeois morality according to which she is confined to a single allotted sexual partner, dull domesticity, and a conventional social life among persons of her own class (she usually is, outwardly, a respectable and well-to-do woman).

Similar to the Happy Hooker, the Adventuress offers a great opportunity for patriarchal films to stage lusty scenes. However, for the Adventuress, there is no ultimate fulfillment in prostitution; indeed, her nymphomaniacal tendencies are typically seen as pathological. Adventuress films typically depict fantasies of self-debasement.

“Alice in Wonderland is a Prostitute City” by Samantha Jade Royds is licensed under CC BY 2.0 DEED.

Archetype twelve: The Junkie

Prostitution is hard work, physically and emotionally, thus it is unsurprising that a large number of prostitutes use drugs to alleviate the sufferings induced by their work (Alexander, 1988). Therefore, many films depicting the prostitute as a heavy user of heroin, cocaine, or morphine simply reflect reality in that respect. The Junkie is the most wretched among all figures of the prostitute, who symbolizes bottomless despair and desperation. She may arouse sympathy among the audience for being the most pitiable of human beings, and at the same time, may provoke their contempt for she is also the most degraded and corrupt.\

Doubtlessly, the Junkie archetype feeds dark male fantasies of the docile sex object that will not resist any form of indignity practiced upon her for she is desperate for that next fix of drug that her pimp or client promises her as a reward for her sex and submission. Some examples of Junkie films are Street Girls (Michael Miller, 1975) and Ginger (Don Schain, 1971). Some of these films act as a cautionary tale about the most wretched conditions that loose and unruly girls may find themselves in. Lê Hoàng’s Gái Nhảy/Bargirls (2003), a “propatainment,” acting both as propaganda and entertainment (Do & Tarr, 2008, p. 65), is a perfect example of this type of Junkie film.

Archetype thirteen: The Baby Doll

The Baby Doll is the adolescent prostitute that embodies contradictory appeals. She is a child who is sexualized to fit the adult world as an erotic object. It is the Baby Doll’s blend of innocence and corruption, the disparity between her sexual and physical or emotional maturity that fascinates and eroticizes. Unlike many other archetypes of the sexual female, the Baby Doll is sexual but not threatening, thus there is an association of eroticism with male power. As young and innocent as she is, the Baby Doll is often a figure of pathos who evokes strong sympathy because she is a helpless victim of forces beyond her control.

Baby Doll films that suggest she chose to enter prostitution voluntarily and is not suffering ill consequences from it, like Iris (Jodie Foster) in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976), assuage the guilt the male audience may experience in indulging fantasies of sex with an underage girl.

Archetype fourteen: The Working Girl

The final of all fourteen representations of the female prostitute in film, as identified by Campbell, is the Working Girl, who perhaps could be seen as a less powerful version of the Business Woman. In Working Girl films, prostitution and the prostitute are deromanticized, deglamorized. She is depicted as an ordinary person doing her job, which is obviously unpleasant in some ways but not necessarily worse than any other jobs under the exploitative regime of capitalism. In these films, prostitutes certainly do not revel in sex work as the Happy Hooker. Work is a grind and they are in only for the money. Films such as Prostitute (Tony Garnett, 1980) and Working Girls (Lizzie Borden, 1986) embolden the female voice, revolving around the subjective experience of their prostitute characters and dismissing all fantasies projected upon them. Working Girl films not only speak against patriarchal society but also of radical feminists who pigeonhole prostitutes as fallen and degraded victims of male society.

Concluding remarks

Male fantasy and psychological needs permeate most of these representations of the prostitute. For example, the Nursemaid represents the dream of possessing a lover/mother/prostitute all in one. The Adventuress opens a channel to her journey of sexual experimentation. The Business Woman dominatrix promises a sex party designed particularly for the masochist. The Captive is the attractive sexual other trapped in men’s power. Meanwhile, the Avenger reflects men’s fear of women bringing retaliation for all the oppression they have suffered at the hands of men, and so on. More often than not, one prostitute character may be the locus of more than one archetype. For example, the Junkie in Bargirls (Lê Hoàng, 2003) turns Avenger when she knowingly transmits HIV to men who rape her.

It is important to note that patriarchal cinema does blame men for women’s plight, but these are obviously “bad male figures” such as pimps, exploitative boyfriends, and brothel owners, not all males and certainly not male-dominated society. By eliminating these few “bad apples,” patriarchal cinema poses a superficial solution and maintains the status quo of patriarchy. The evil pimp or drug dealer is, of course, punished in the end, and narratives are made in ways that make viewers identify with law and order (through, for example, a detective investigating a prostitution ring), which again preserves the status quo. As for the prostitute, oftentimes, she is either married off or killed off, unless the film is a feminist-inflicted product.

References

Alexander, P. (1988). Prostitution: A Difficult Issue for Feminists. In F. Delacoste & P.

Alexander (Eds.), Sex Work: Writings by Women in the Sex Industry. London:

Virago.

Campbell, R. (2006). Marked women: Prostitutes and prostitution in the cinema. University of

Wisconsin Press

Films mentioned

Ashani Sanket/Distant Thunder (Satyajit Ray, 1973)

Casino (Martin Scorsese, 1995)

Casque d’Or (Jacques Becker, 1952)

Cô Gái Trên Sông/Girl on the River (Đặng Nhật Minh, 1987),

Dirnentragödie/Tragedy of the Street (Bruno Rahn,1927)

Ginger (Don Schain, 1971)

Gái Nhảy/Bargirls (Lê Hoàng, 2003)

Leaving Las Vegas (Mike Figgis, 1995)

Prostitute (Tony Garnett, 1980)

Street Girls (Michael Miller, 1975)

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

The Bacchus Lady (Lee E-yong, 2016)

The Best House in London (Philip Saville, 1969)

The Happy Hooker (Nicholas Sgarro,1975)

Working Girls (Lizzie Borden, 1986)

Xiao Fengxian/The Little Phoenix (Kuang-Chi Tu & Hsin-Po Hsu, 1953)