A Historical-Institutional Analysis of the Politics of Power in the Philippines

Article by Geoffrey Rhoel C. Cruz

Abstract:

Looking at the characteristics of Philippine politics from its inception, Philippine democracy is about securing vested personal interests at the expense of general welfare. Ever since, it was a quest for personal security, and ensuring security to trickle to all other aspects of social life. Apparently, the presence and persistence of such a political set-up has hampered the growth and development of the country. Through a historical-institutional analysis, this article investigates the historical narratives that contributed to the present state of Philippine politics. Similarly, this study analyzes the factors that hamper political development in the country. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson explained that the main determinant of differences in prosperity across countries are differences in economic institutions that depend on the nature of political institutions and the distribution of political power in the society, hence, addressing the problem of development entails change in institutions that affects the distribution of de jure political power. The findings suggest that such change needs to be complemented by changes in the sources of de facto political power of the elite and reductions in the benefits the political incumbents have in intensifying their use of de facto political power. The state needs to be empowered to break free from the shackles of elite bureaucracy and minimize their influence on the current state of politics in the Philippines. Until such, genuine development will be hampered and political maturity will always remain far from reality.

Keywords: Clientelism, Patronage Politics, Patron-Client, Political Power, Political Institutions

Header Image by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA

I. Introduction

Philippine political dynamics has been perceived as an endless drama with an unsurprising finale. First, it has been observed as the contest between the rich and the poor. Second, it has been considered as the rivalry between good and evil. Third, it has been pondered as the battle between seasoned politicians and neophytes.

Moreover, three aspects characterize present Philippine local political dynamics; it’s all about trust, loyalty and security with the first two values given least importance in relation to the third. In the beginning, the first two values are given greater primacy but later on, the third value will manifest complete dominance such that old foes are becoming allies against emerging foes. More than that, it appears that blood relationship is becoming immaterial as siblings and relatives become political rivals as well.

On one hand, the security aspect of Philippine local politics is the offshoot of a weak state and weak political party system where in political dynamics are highly personalistic and clientelistic. Whenever the political vacuum created by elections threatens political security, party switching becomes pervasive thus comprising trust and loyalty.

On the other hand, in ensuring political security, it has been the practice of local politicians to pass on the bastion of power to somebody whom they trust the most. It cannot be any better than their relatives. Considering the term limit attributed by the constitution as a way of avoiding political monopoly, incumbent politicians serving their final term will make sure to endorse the throne to his/her successor professing that it is an assurance that there will be continuity of programs and projects already started and will work on the gains of the incumbent, thus facilitating the growth and tolerance of political dynasties.

As such, looking at the characteristics of Philippine politics from its inception, Philippine democracy is about securing vested personal interests at the expense of general welfare. Ever since, it was a quest for personal security, and ensuring security to trickle to all other aspects of social life. Apparently, the presence and persistence of such a political set-up has hampered the growth and development of the country.

Through a historical-institutional analysis, this article investigates the historical narratives that contributed to the present state of Philippine politics and analyze the factors that hamper political development in the country. Specifically, this will answer the central question of “How historical and institutional factors contributed to the development of political power in the Philippines?”.

II. Research Framework

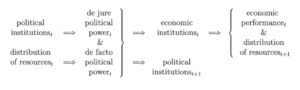

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2008) explained that the main determinant of differences in prosperity across countries are differences in economic institutions that depend on the nature of political institutions and the distribution of political power in the society, and that to solve the problem of development will entail reforms of such institutions.

It has been considered that economic development is not an end in itself but instead has been a catalyst for other social development to take place. But to facilitate economic development, Acemoglu and Robinson suggested that proper institutions, defined by North (1991) as the rules of the game in a society that serves as the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction, are necessary to maintain the balance of power (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2008: 2). In particular, Acemoglu and Robinson emphasized the relationship between three institutional characteristics including (1) economic institutions; (2) political power; and (3) political institutions as key points in growth and development.

Accordingly, economic institutions are relevant because they shape the incentives of key economic actors in society such as business elites who holds control over the distribution of economic gains and resources thus compelling outmost bargaining power. The dilemma lies in the fact that not all individuals and groups prefer the same set of economic institutions because it does not apply equally. This triggers tension and conflict of interest, wherein the deciding factor becomes the political power of the differing groups. Moreover, political power comes from two possible sources, de jure and de facto political power. The former refers to power that originates from the political institutions in society, while the latter refers to power that even if they are not allocated by political institutions it obtains compelling political force through the economic resources available to the group (Acemoglu and Robinson 2008: 6-7).

Acemoglu and Robinson (2001, 2008) suggested that political institutions provide de jure political power and those who hold political power influences the evolution of political institutions thus will likely opt to maintain the political institutions that give them political power for they greatly fear the redistributive consequences of political change. On the contrary, a rich group relative to others will likely maintain its de facto political power and push for economic and political institutions that are favorable to its interest.

Figure 1: Political Power Framework by Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2008).

The Political Power Framework provides that in order to maintain a balance of political power, successful reforms necessitate changes in both de jure and de facto power. Such that taking away one factor without altering the balance of power in society can lead to the replacement of one factor by another thus producing a see-saw effect (Acemoglu et al 2003 in Acemoglu and Robinson, 2008: 12). With this, a successful reform entails change in institutions that affects the distribution of de jure political power. However, such change needs to be complemented by changes in the sources of de facto political power of the elite and reductions in the benefits the political incumbents have in intensifying their use of de facto political power (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2008: 19-20).

III. Discussion

In Economics, the Equilibrium Method suggests that for prices to be stable, supply and demand should balance each other. As applied to the concept of political power struggle, the rule lies in finding the constant balance to always arrive at the equilibrium point such that at the end of the day the utilitarian principle of greatest good on greatest number will always be feasible. Hence, looking at the different stakeholders and the roles they play in Philippine political dynamics reveals the loopholes and state of imbalance of politics and democracy in the Philippines.

III. Clientelism and Patronage Politics

On one hand, the most popular concept in explaining Philippine politics is structured around the demand aspect of power as provided by the framework developed by Carl Lande (1965) explaining the Philippine political drama in the light of the patron-client framework (PCF). The PCF suggests, “Philippine politics revolves around interpersonal relationships – especially familial and patron-client ones – and factions composed of personal alliances (Kerkvliet 1995: 401 in Teehangkee 2012b: 186). The key component of the PCF lies in the concept of clientelism, characterizing a relationship in which an individual of higher socio-economic status (patron) uses his influences and resources to command power over a person of lower status (client), who in return is expected to offer support and assistance to the patron (Teehankee 2012b: 187).

Such dyadic alliance commands a reciprocal relationship between the actors involved and entails an informal but binding agreement of mutual development. This relationship was first introduced during the pre-colonial era, in which debt peonage and sharecropping [1] became the basis of mutual relationship between tillers of the soil and the landlords (Doronila 1985: 100). This relationship became the foundation of the community structure such that the members were expected to work and fight for the leader and in exchange the leader was expected to lead and defend the tribe against outside threats and keep the internal factions in the tribe in control thus avoiding chaos at all times.

This relationship was fostered by the arrival of the Spaniards, which introduced a formal set up of governance in the form of barangay governance. Though much alike, the greatest difference lies in the principle of subordination and the establishment of a superior authority in the character of the king of Spain and the governor general assigned to the Philippines. Nevertheless, the governor general does not really possess compelling mandate because authority was appointed rather than through consent. Likewise, the base of the governance structure follows the same pattern in which the village chief or cabeza de barangay was also an appointed authority. Understandably, authority was limited to those with Spanish bloods and Filipinos were considered as mere subordinates under the pretense of mutually beneficial relationship.

But the downfall of the Spanish governance in favor of the American governance made things more complicated, turning it into a political drama. Working on the premise of democracy, the Americans granted greater Filipino participation in governance allowing Filipinos to be active participants in day-to-day operations of the government paving the way for the first national democratic elections in 1907. This paved the foundations of electoral party systems with a narrow class base that was greatly dominated by the landlords (Doronila 1985:101).

Apparently, the 1901 municipal elections further emphasized the existing patron-client relationship that characterized Philippine politics. The election was limited only to the members of the principalia or the men in power during the Spanish era, which set the parameters for the dominance of the landed elites in forthcoming elections. Such that the establishment of the Philippine Assembly in 1907 opened the way for member of the principalia to aspire for national power as a way of securing their vested interest, which will soon become the foundations of what has been recognized as cacique democracy. Cacique are the local leaders possessing warlord-like powers whose authority were further institutionalized because of the political power they hold (Anderson, 1988). As argued, they were for the first time forming a self-conscious ruling class that visualizes a hold on the Congressional control of the purse as a way of guarantee of their property and political hegemony (Anderson, 1988: 11). Nevertheless, these local elites will soon comprise the major building blocks of national elite that dominated the national legislature in 1907 while extending their autonomy at the local level (Hutchcroft 2000: 292 in Teehankee 2012b: 191).

Together with the rise in power of the principalia or landed elites is the institutionalization of the PCF as the key defining moment in Philippine political drama. Beginning from the 3rd Republic up to present, landed elites or what has been tagged as the trapos (traditional politician) have dominated the political landscape by capitalizing on personality politics through short-term benefits. Nonetheless, such provided the predicament for one of the most tried and tested formula in Philippine electoral campaign.

Moreover, Machado (1974: 1183) suggested that the traditional concept of PCF transforms as the socioeconomic situation changes, such that the emergence of “new men” or non-landlord professional politicians has been observed. But still the success of the “new men” was attributed to political machines that offered benefits to their members such that the existing landscape implies a reciprocal relationship based on short-term benefits, in which aspiring politician must invest to build a bountiful war chest to guarantee a return of investment in the future. Aspinall et al (2016: 194) have reiterated the role of money as catalyst. They have noted the practice of vote buying as a long-established part of elections in the Philippines and have considered its essence to campaigning.

Considering the developments in Philippine political dynamics, the demand-pull aspect is very superficial such that the demands imposed by the client need to be provided imperatively by the patron to guarantee support and assistance thus giving prominence to the rise of de facto political power. Generally, those who hold de facto political power will likely use it to secure benefits at the present as well as in the future because individuals not only care about economic outcomes today but are also much interested in the future. But their use of de facto political power will be limited because those who hold de jure political power at present time makes the decisions for the future, hence reveals the imbalance state of politics and power in the Philippines.

Weak State, Strong Society, Captured Democracy

On the other hand, the least popular concept that defines Philippine politics constituting the de jure source of political power is structured around the idea of state-centered approach suggesting the presence of a “weak state, strong society” as expounded by the framework popularized by Joel Migdal (1988). In relation to this, Gunnar Myrdal (1968) likewise suggested the idea of a “soft state” with emphasis that the state was not created to promote and manage development but was established to secure the interests of colonial power in terms of law and order. Paul Hutchcroft (1998) further insinuated, “access to the state apparatus remains the major avenue to private accumulation, and the quest for ‘rent-seeking’ opportunities continues to bring a stampede of favored elites and would-be favored elites to the gates of the presidential palace.” As such the state serves as the war booty in the political tug-of-war.

The supply aspect of Philippine politics focuses on the structure of the state as it was first established and has continuously evolved through time. Starting off with the establishment of Philippine bureaucracy as an “extractive state” for the purpose of extraction of resources with little protection to private property and minimal checks and balance against the government. Moreover, the presence of an appointed governor general during the Spanish colonization with the utmost authority apparently led to the weakening of the state. As the governor general operated based on whims and with prejudice, it further diminished the significance of the state.

As the control of the state was transferred from Spanish to American hegemony, little empowerment was shared to the state. Still it remains to be an apparatus of the American governor general with minimal significance. Likewise, the absence of accountability continuously eroded the power of the state as majority of the American democratic principles of governance were inherited by the Philippines except for the principle of federalism. The unitary and presidential form of government further consolidated the power of the state to the executive over the legislative and the judiciary. Thus as the first electoral activity was initiated, members of the society clashed with one another to get a bigger piece of the state to ensure access to its resources and guarantee security of one’s properties.

Moreover, Teehankee (2012b: 187) emphasized that these contributed to the development of weak political parties in the Philippines who are not seeking for mass membership but only for mass support. Hence, the Philippine state has been characterized as being ‘weak’ or ‘captured’ in competing and diverse social interests. Doronila (1994: 48) attested to this claim saying that the Philippine state has limited capacity to impose its will and to carry out policy reforms.

Additionally, the concept of “pork barrel politics” provided access to state’s budgetary spending intended to benefit limited groups. The credit claiming and political machinery building capacity of pork barrel translates into a political advantage that can lead to re-election. In some instances, the system has been abused in order to penalize or neutralize political opposition thus committing the practice of political turncoatism as a normal behavior. It has been observed that party membership in the Philippines is transient, fleeting, and momentary as most political parties are active only during election season (Teehankee 2012a: 196, 2012b: 201).

Post-martial law events witnessed continuous political party switching from the losing party (minority) to the winning party (majority) thus further contributing to the deterioration of political institutions. Just like the old drill, some political parties were disbanded while others decided to merge with the dominant party causing internal control issues leading to party detraction of neglected senior members thus creation of new political party that will cater to their interest; hence a vicious cycle.

Apparently, Philippine political party system “continues to be candidate-centered coalitions of provincial bosses, political machines, and local clan, anchored on clientelistic, parochial, and personal inducements rather than on issues, ideologies, and party platform” (Teehankee, 2012b: 208). It is also the apparent reason for the prevalence of ad hoc political parties as well as mushroom parties, ideological gap-filling parties, splinter parties exiting from other parties, and special issues parties during the post-Marcos period.

IV. Conclusion

The rich colonial history of the Philippines has characterized the current conditions in which present political institutions persist. Understandably, successful reforms will be rendered fruitless without considering the dynamics of political development in the country, thus it has always been the idea of extraction of resources for personal benefit and assuring security of those benefits in the future. Clearly, this sustains not only the political but economical imbalance as well.

Ever since, the Philippines has been a representation of Paul Hutchcroft’s ‘booty capitalist’. According to Hutchcroft (1998), in booty capitalism a powerful oligarchic business class extracts privilege from a largely incoherent bureaucracy and less likely to foster new social forces able to encourage change from within. Since elections require huge political and financial war chest, the political vacuum created by elections and the scrambling for power is taken advantage by the oligarchs to best position their vested interest. Thus the ruling class captures the state. Anderson (1988) describes this as the prevalence of cacique democracy in the Philippines. As the pendulum keeps on swinging in every elections, the ruling class has to make the right decision on which card to place their bet to ensure political survivability making politics highly personalistic and clientelistic.

As such, understanding underdevelopment in the Philippines requires analysis of factors that push a society from bad to good political equilibrium. Such institutional approach provides that if we can understand the determinants of political equilibria, better institutional interventions can be designed that will properly address all concerns thus avoiding the dilemma of a possible seesaw effect. Walden Bello (2004) once suggested that could it be that the Philippines has been barking on a wrong tree after all, thus recommending that the alternative to the political economy of anti-development that currently reigns in the Philippines is a strong state that promotes the development and disciplines the elite and the private sector reflecting symmetry between de jure and de facto political power in the country.

In some way, the aspects of demand and supply and the concept of de jure and de facto political power have represented the dynamics of Philippine politics. The demand aspect represents the need that motivates the dominance of the patron-client framework, while the supply aspect manifests the weak character of the state. As the two aspects continuously operate, the possibility for disequilibrium is always imminent making politics a personal issue rather than utilitarian. Just like in Economics, the law of demand and supply requires symmetry to arrive at the equilibrium point such that if the supply is less than the demand there will be ‘shortage’ and vice-versa ‘surplus’ is forthcoming thus both affecting the stability of the economic system. Consistent with politics, it is imperative to always achieve balance to avoid disruption in the political system. On one hand, ‘shortage’ implies captivity of the state as it serves as war booty particularly during elections, subject to the discretion of the winning party. On the other hand, ‘surpluses’ imply a weak state that is always amenable to the demands imposed by the dominant political party. It is tantamount to a pendulum that consistently swings toward the dominant party.

Therefore, there is a need for state empowerment. As emphasized by the iron law of oligarchy (Michels, 1962) that when new groups mobilize or are created in the process of socioeconomic change, they simply replace preexisting elites and groups and behave in qualitatively similar ways. Acemoglu and Robison suggested that replacing only one factor by another might do little improvement such that they are recommending that de jure and de facto power must be simultaneously reformed (2008: 20).

Until such time that we have a state that can finally escape from the shackles of elite bureaucracy, if the elites perceived that extending support to a certain political force in the society remains to be a viable investment, thus we might end up still being barking at the wrong tree.

Notes

- Debt peonage and sharecropping characterized the initial relationship of the tenant to the landowner. Since harvest season does not come immediately, tenants were compelled to loan money from their landowner for the tenant’s daily upkeep. When harvest season comes, all the yield will be collected by the landowner as payment for the tenant’s existing loans. This places the tenant in a debt trap cycle forcing the tenant to a peonage work system to pay off their debts. On the other hand, sharecropping is an arrangement between the tenant and the landowner in which both parties agree to a crop sharing scheme. However, since the landowner usually charge rent for the use of his land which the tenant cannot afford to due to lack of capital funds, the tenant is forced to accept a less favorable scheme.

References:

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2001). A theory of political transitions. American Economic Review, 91, 938-963.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2008). The role of institutions in growth and development (Commission on Growth and Development, Working Paper No. 10).

Anderson, B. (1988). Cacique democracy and the Philippines: Origins and dream. New Left Review, 1(169), 3-31.

Aspinall, E., Davidson, M. W., Hicken, A., & Weiss, M. L. (2016). Local machines and vote brokerage in the Philippines. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 38(2), 191-196.

Bello, W. (2004). The anti-development state: The political economy of permanent crisis in the Philippines. Department of Sociology, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines.

Buendia, R. G. (1989). The prospects of federalism in the Philippines: A challenge to political decentralization in a unitary state. Philippine Journal of Public Administration, 33(2), 121-141.

Doronila, A. (1985). The transformation of patron-client relations and its political consequences in postwar Philippines. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 16(1), 99-116.

Doronila, A. (1994). Reflections on a weak state and the dilemma of decentralization. Kasarinlan, 10(1), 48-54.

Geddes, B. (2007). What causes democratization? In C. Boix & S. C. Stokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics (pp. 297-316). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hutchcroft, P. (1998). Booty capitalism: The politics of banking in the Philippines. Cornell University Press.

Lande, C. H. (1965). Leaders, factions and parties: The structure of Philippine politics (Southeast Asia Monographs, No. 6). Yale University.

Machado, K. G. (1974). From traditional faction to machine: Changing patterns of political leadership and organization in the rural Philippines. Journal of Asian Studies, 33(4), 523-547.

Michels, R. (1962). Political parties: A sociological study of the oligarchical tendencies of modern democracy. New York, NY: Free Press.

North, D. (1991). Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97-112.

Teehankee, J. C. (2009). Citizen-party linkages in the Philippines: Failure to connect? In Reforming the Philippine political party system (pp. 23-44). Pasig, Philippines: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Teehankee, J. C. (2012a). The Philippines. In J. Blondel & T. Inoguchi (Eds.), Political parties and democracy: Western Europe, East and Southeast Asia 1990-2010 (pp. 187-205). Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Teehankee, J. C. (2012b). Clientelism and party politics in the Philippines. In D. Tomsa & A. Ufen (Eds.), Clientelism and electoral competition in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines (pp. 186-214). Oxford, UK: Routledge.