Die Behandlung, Tenderness of the In-between

Article by Chia-Ying Shen

Abstract:

This essay foregrounds women’s bodies in relation to medical production in the context of Taiwanese colonial history, further circulating around the theme of knowledge in conflicts under the condition of planetarization (See Y. Hui , 2022, This Strange Being Called the Cosmos). In the face of the permeated inseparable power-knowledge, particularly technological knowledge originating from one region, the artist attempts to outline the disconnection of the somatic self and the bodily representation, the chasm between the meaningful presence and the technological artifacts. The aim of this essay is to relocate and retrieve the agency of the body on the planetary scale concurrently with the omnipresent medical implementation. On this note, borrowing the German word “Behandlung” from Gadamer, encompassing both the “handling” and the “hand”, this work speaks of the treatment beyond the modern technique.

Keywords: woman’s body, machine, care

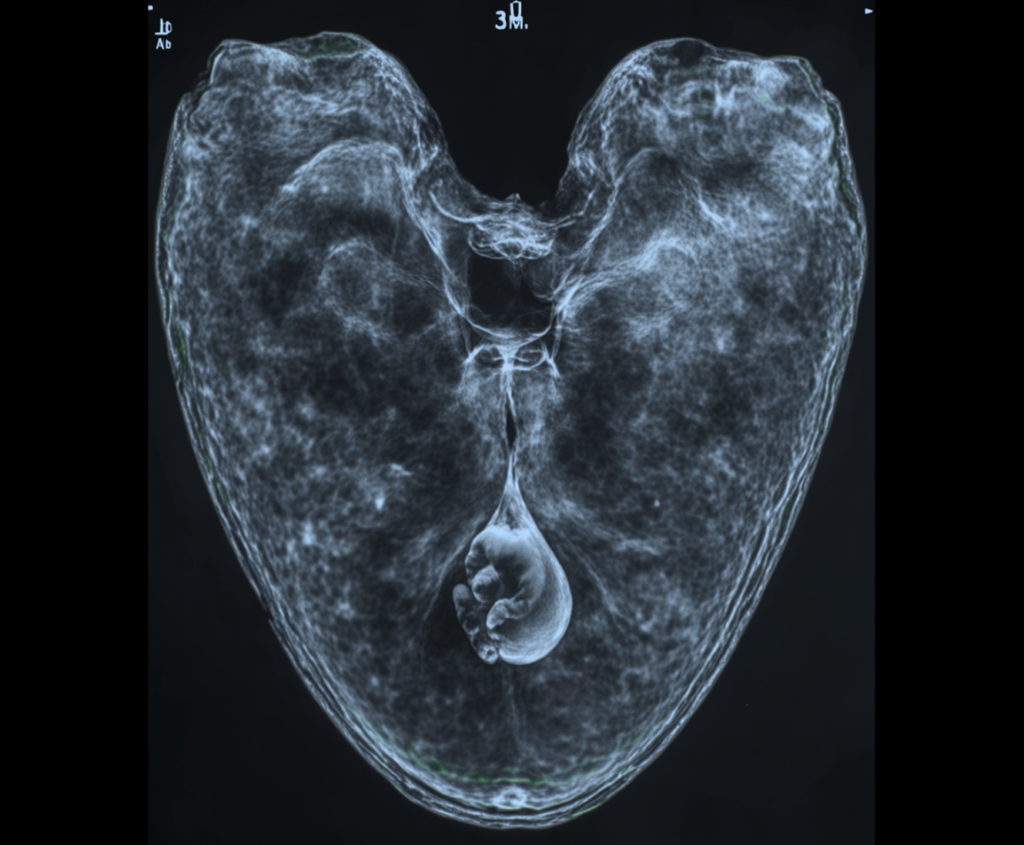

Header Image: Original photograph by the author

Introduction

In July 2023, I exhibited an installation work of a pile of menstruation cups— fragile, hand- made, broken wax cups, smaller than the average size on the market, abandoned in the corner of the room. The inspiration for this work derived from the attempt to purchase a menstrual cup in Germany as chronic pad user, alike to many other women in Taiwan. A serial question was raised, as I looked at the commodity on the shelf. Frankly, I doubt myself would be able to put the silicone object inside my vagina due to the size; moreover, where does the idea of placing an object into women’s bodies come from? How come I have the impulse to buy such a product, even though I am physically repulsed by it?

The result of myself facing menstrual cups in the store or going to a gynecologist for installing IUD (intrauterine device) manifests a facade of “unilateral globalization”, in Yuk Hui’s words, the “particular epistemologies [from a] regional worldview to a putatively global metaphysic” (2017). Or to put it bluntly: is it a continuation of today’s European expansion by another name, aided by scientific and technological resources?

Of course, there are obvious reasons that a sense of misfit is generated: the physical aspect, and the fact that the center of my life has been uprooted and transplanted. However, the process of the untangling the misfit is twofold. First, the interplay between different colonial systems and the medical infrastructure they brought to Taiwan. Tens of millions of women’s bodies were subjected to the transformation from semi-colonial missionary medicine to Japanese medical modernity, following the health-care system tethered to the democratic resistance under the KMT party. Second, the discontinuity between the self and the world, derived from the rift and incoherence of the medical artifacts in action and the body they act upon.

It is impossible for me to comprise every perspective thoroughly in this essay. This work is rather an attempt to exhibit my train of thought, pose questions awaiting answers, speak as a Taiwanese woman of Han origin, as an art practitioner, and in an effort to make accounts for such.

Science on Our Horizon

To begin delineating science and technology in a multiply located condition, we need to take the standpoint(s) of the Other, and critically reassess the Northern (European) scientific and technological tradition (Harding, 2008). That is to say, modern science is far from innocent or neutral. As Sandra Harding contended, there is a causal relation between European expansion (“The Voyages of Discovery”) and the emergence of modern science in Europe. Moreover, she mentioned in John M Hobson’s study, how European’s identity (“Christendom”) was formed explicitly against Islam and suppressed the borrowings from Asia, until as recently as the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth (the former continues to be so today). And further, so-called “development” policies were initiated in the 1950s, which were conceptualized as the transfer of First World scientific rationality and technical expertise to the “underdeveloped” societies (Harding, 1998).

On this ground, the challenge now is how we can seek accounts for other, “silent” groups in history—peasants, women, subalterns (Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?”)? How can we operate on a small-world perspective, the partial, locatable knowledge (Reed, 2019)? And importantly, how to regain the solidarity in politics and foster shared conversation in epistemology (Haraway, 1988)?

Before situating in what Patricia Reed called “the big-world”, a horizonless world (Reed, 2019), a nested account of departure, we shall first locate ourselves, confirm our horizon. That is not to be lost and perplexed in the atlas of communicative dimensions of epistemology, or simply as we are already in it. In other words, confrontation with the planetary condition or planetarization reproduces the sense of Heimat (Hui, 2024). Yuk Hui put it precisely, “…to overcome modernity meant first of all to adopt an orientation toward Heimat.” (p.28) He describes Heidegger becoming a “state thinker,” as did his disciples such as Keiji Nishitani, even though Heidegger’s distancing from the Other. The Heimat, the feeling of home is always in constant movement. It recounts a more malleable and mobilized standpoint for longing, involved with the impending, or at times, no where to be found.

Only by finding our affinity in the discrete world, we can aggregate and confront Heimatlosigkeit, the feeling of misfit, and perhaps, overcome the mono-humanist version of being inflicted on. One of the methods that can be applied here is “the practice of memory” (Johnson, 2021, p.194). For example, the artwork “kith and kin” by Archie Moore, a First Nations Australian artist, creates a memorial of Aboriginal Australian kinship and sovereignty, drawing a genealogical chart according to his Kamilaroi, Bigambul, British and Scottish lineage. Walking through the family tree drawn across the walls and ceiling, and the stakes of death reports of Indigenous Australians, enable us as foreign viewers to share the same horizon as others in different temporality, encountering the living beings here and there, of the past, present and the future.

I couldn’t help but think of what and how a woman is taught by her mother. What are the untold stories of the women who traveled to Tokyo in order to study medicine in 1933? What about the midwives? The dead bodies sacrificed on the surgical tables to allow the success of the procedures like dilation and curettage (D&C) (Fu, 2005).

We Talk Gossip

We can orient ourselves by talking gossip into this cartography of science. Gossip nowadays has been presented as an “evaluative talk about a person who is not present”, serving a distinct meaning from rumor, which is “an unconfirmed statement or report that is in widespread circulation” (Chaikof, et al., 2019). In models of literature, gossip can establish a constructive social norm, where a group of people is influenced by certain values, experiences, or methodology. In Early Modern England the word “gossip” referred to companions in childbirth, including midwives and other women in the room of during labor. As Pierson and Hughes suggested, giving birth used to be a social event, the pregnant female relatives and neighbors would gather, sharing personal experiences, anecdotes, and medical knowledge through chattering. In this sense, the gossip circulates in a decentralized structure, distributing organically among women, and their relationship with bodies is built upon this communal tenderness.

Motherhood or mothering is not confined to biology. How information is distributed regarding menstruating reflects the decentered role of motherhood in the menstrual process. “I told her about it and she referred me to my aunt who would assist me.” … women are not only the figureheads of a family but also imbued with moral power. (Perianes and Ndaferankhande, 2020, p.429)

Perianes and Ndaferankhande argued that in Malawi, East Africa, there is a multitude of culturally specific ceremonies that celebrate menarche as entering adulthood. In the context of Malawi, from a matrifocal perspective, femininity refers to women’s power and status, which emerges from the center of the family, motherhood, and affiliation with other groups of women. The gossip functions as a link between different nubs, reinforcing the power and autonomy of women’s bodies. In thinking of early Taiwanese society (in the perspective of the hegemonic Han ethnicity), which is patriarchal, rather than matriarchal as in Malawi or Taiwanese indigenous groups Amis and Puyuma; however, interestingly, the way that knowledge and treatments disseminated in traditional Han medicine (中醫) for menstruation, giving birth, and conditions regards to Qi (氣) and blood (two basic bodily fluids) was by the gossip among women and traditional midwives (產婆). This social gender dynamic compelled the women to address those conditions obliquely and through the verbal network. This autonomous unit of femininity embodied by the role of the traditional midwife, served as a knower and an agent of knowledge about themselves. The network of gossip shared by women existed in different social reality prior to the arrival of colonial medicine, where the role of “the knower” had been transferred to authority (doctors, were mainly men).

Be In-between

Thus, the knowledge of one’s well-being (the concept of health), is an interpersonal consensus that is acknowledged and shared by the being within the locally cultural program. This consensus reflects the art of eating, sleeping, living, and dying, as cultural health. Whether the technology was received as a reactionary consequences between tradition and modernity or a fanatical acceleration, there is very little value in taking our cultural health into consideration; the knowledge bounded to one society, was homogenized. The cosmopolitan medical civilization that colonized and permeated until today, as Ivan Illich argued, transforms the experience of pain (1976). When nervous stimulation “pain sensation” results in a distinct human experience accrued from personality and culture, it differs from mere sensation but is uniquely called “suffering”. In Illich’s words, “Medical civilization, however, tends to turn pain into a technical matter and thereby deprives suffering of its inherent personal meaning” (p.46). So what does every inspection in a gynecologist clinic mean to me? When I look at the black-and-white ultrasonic image on the screen, what does it tell me? Does the personal data documented on a single DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) file speak about my suffering? The second layer of misfit is generated from the significance of artifacts and actions, and the method in which they convey. If the answer to the question is positioning a decentered version of human(user) on a planetary scale, then how can we detect the problem of human- machine deep asymmetries, which is derived from the mis- or different understanding of dehumanized artifacts and actions underway?

Moreover, as all radiological images now are stored in digital format and further being used in training AI models in facilities, dedicated to assisting physicians in the process of diagnosis, these questions persist. In Fritz Kann’s famous illustration “Der Mensch als Industriepalast”, human flesh and organs are replaced by rigid compartments, metallic tubes, and functional objects; there are even tiny figures working inside the corporal structure as laborers. The visualization alludes to a fascination with a machinized, optimized body. But as we look at the image now in the age of digitalization, an image of the human is constructed by algorithms, data analyses, and forecasts of artificial intelligence. Should we surrender our corporality and the continuation of interaction with the environment to a reductional self by an image? In animation production, “pose-to pose” or “in-between animation” plays a crucial role in the whole animating process, where animators have to complete the frames of movements from one keyframe to another in order to create “life” from static image. Having worked with 2D animation in the past, I experienced it as indeed the most time- and labor-consuming step of realizing and materializing ideas. Now, we can also understand this “in-between” as what concretes the being of the whole world and being with others. The betweenness of the senses, the touches to the localizing in the body, and the holistic comprehension of our existence are threatened and obliterated. Adopting Fuchs’s “embodied anthropology” (2021), Francesca Brencio proposed the term “embodied care”, focusing on the interconnection between the caregiver and the caretaker. She mentioned how powerful “eye contact” is, when a health workers engaged with Alzheimer’s patients. “The significance of their connection derives not from semantic content but rather from the meaning their bodies directly convey”. (cf. Kontos, Naglie, 2009, p.697) What I received from a skilled masseur, was that she used her hands to perform treatment on my whole body while chatting with me about my personal life. The betweenness endows the technique to reify and traverse from one being directly from another being; and caring is grounded in the trust on the other person, just as the gossip tellers, their relation with the world is mediated through the interconnected knowledge map, rather than the interactional competency of a machine.

Conclusion

Once again, I have to go back to my Heimat, our fluctuated horizon, to find the commons in our knowledge, to reorient and relocate. Reflecting on the contemporary medical scene in Taiwan, it is a convergence influenced by the antecedent and colonial power and sequentially geopolitical conditions. We as patients have always access to state-of-the-art clinical equipment for surgery or diagnosis; whereas 國術館, traditional Han massage, and acupuncture are jointly near at hand. The paradox in the post-medical civilization and modernization era is suggested in the description of Heimat. That is the “not yet” and “no where to be found”, the alternating standpoint of longing for the accustomed. It has been clear that there is no completion of a planetary scale with the augmentation of the medical or technical artifact and infrastructure; simultaneously, there is no static local science with the essentialist idea on the methodology or formality on our horizon. It reproduces and becomes a commensurable state in small dimension, or to an opaque compound that is hard to be gleaned. That said, a sense of misfit still lingers; the quest of being at home is never- ending.

References:

Bailey, C., & Honderich H. (2023, July 15). SAG strike: Why Hollywood actors have walked off set. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-66208226.

Brooker, C. (Writer) & Pankiw, A. (Director). (2023, June 15). Joan Is Awful (Season 6, Episode 1) [TV series episode]. In C. Brooker (Executive Producer), Black Mirror. Netflix.

Brunton, F., & Nissenbaum, H. (2013). Political and Ethical Perspectives on Data Obfuscation. In M. Hildebrandt & K. De Vries (Eds.), Privacy, Due Process and the Computational Turn, 164–188. Routledge.

Brusseau, J. (2020). Deleuze’s Postscript on the Societies of Control: Updated for Big Data and Predictive Analysis. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 67(164), 1-25.

Deleuze, G. (1992). Postscript on the Societies of Control. In October, 59, pp 3-7.

Galic, M., Timan, T. and Koops, BJ. (2017). Bentham, Deleuze and Beyond: An Overview of Surveillance Theories from the Panopticon to Participation. Philosophy and Technology, 30, 9-37.

Gomez-Uribe, C. A., & Hunt, N. (2015). The Netflix recommender system: Algorithms, business value, and innovation. ACM Trans. Manage. Inf. Syst. 6 (4), Article 13, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1145/2843948.

Haggerty, K., & Ericson, R. (2003). The Surveillant Assemblage. British Journal of Sociology, 51(4), 605–622.

Mann, S. (2004). “Sousveillance”: Inverse Surveillance in Multimedia Imaging. Multimedia ’04: Proceedings of the 12th Annual ACM International Conference on Multimedia. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1027527.1027673

Patten, D. (2023, September 26). WGA Chiefs Ellen Stutzman & Meredith Stiehm Q&A: “Transformative” Deal For Hollywood, Solidarity With SAG-AFTRA & The AMPTP’s “Failed Process”. Deadline Hollywood. https://deadline.com/2023/09/writers- guild-leaders-interview-end-of-strike-1235557011/

Seecampe, A., & Söffner, J. (2024). A Postscript to the “Postscript on the Societies of Control”. SubStance, 53,(2) 75-85.

UK Parliament. (2019). Netflix—supplementary written evidence (PSB0069). The Future of Public Service Broadcasting Inquiry. PSB0069 – Evidence on Public service broadcasting in the age of video on demand

Wilde, O. (1891). Intentions. UK, Methuen and Co, Ltd.

Writers Guild of America. (2023, September 25). Memorandum of Agreement for the 2023 WGA Theatrical and Television Basic Agreement. https://www.wga.org/uploadedfiles/contracts/2023_mba_moa.pdf

Writers Guild of America. (2023, September 25). Summary of the 2023 WGA MBA. https://www.wga.org/contracts/contracts/mba/summary-of-the-2023-wga- mba

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Profile Books.