A Case Study of the Bourgeoisification of Bengali Theatre and the Left

Article by Suddhayan Chatterjee

Abstract:

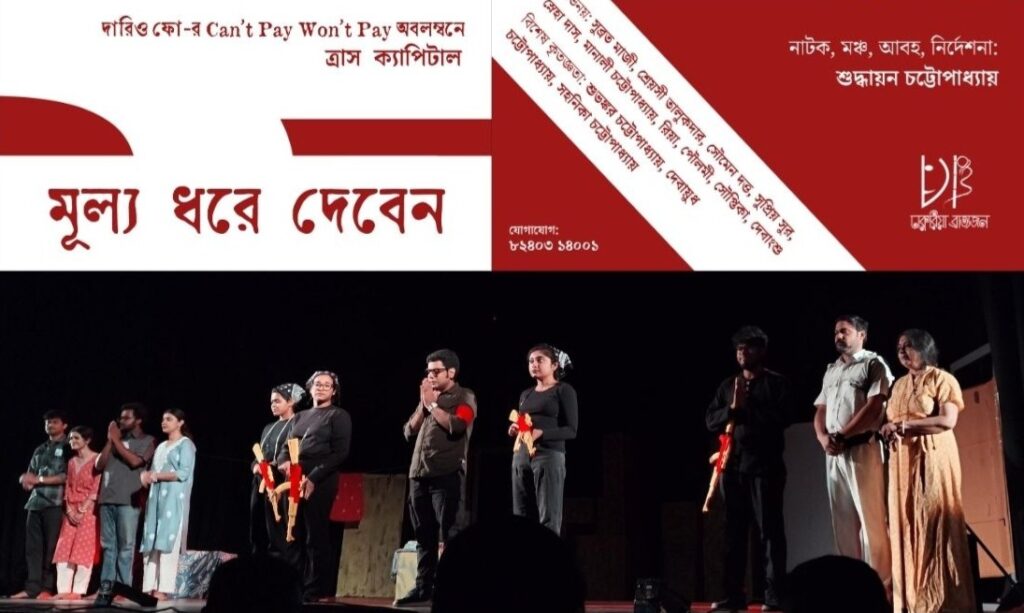

The article examines my adaptation of Dario Fo’s Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay! in the context of contemporary West Bengal. Fo’s farcical mode, rooted in the Italian struggles of the 1970s, resonates powerfully with the present moment marked by unemployment, price hikes, and agrarian distress in the aftermath of the pandemic. The adaptation, Tras Capital – Mulyo Dhore Deben, explores how contract farming, corporate monopolies, and the complicity of state policies intensify dispossession for both farmers and workers. Through farce, music, choreography, and digital scenography, the play foregrounds the contradictions of democracy under neoliberal capitalism. Analysing my adaptation as a case study of bourgeoisification, the article demonstrates how Bengali theatre has increasingly oriented itself toward middle-class concerns, leading to an estrangement from its working-class origins; in doing so, the article brings forth how the decline of the Left in Bengal and the decline of the Bengali Group Theatre Movement are symptomatic of one another.

Keywords: Bourgeoisification, Bengali Group Theatre, Left Politics in Bengal, Dario Fo Adaptation

Header image, combining the original poster of the production with a curtain call photograph, designed and provided by the author. From Tras Capital – Mulyo Dhore Deben (“Terror Capital – Fix the Prices”).

Introduction

From the middle of October 1974, sudden attacks began to erupt in various markets and supermarkets across Milan, where people looted goods or, in protest against the rising prices, forced shop employees to sell commodities at their old rates. In most cases, the police arrived on time, arrested the perpetrators, and brought the situation under control; yet reports of such incidents continued to surface almost every day. From the leaflets left behind, it became clear that those acts had been carried out by a Maoist organization (Servire il popolo).

“The goods we took were already ours, just as everything else is ours because we have produced it through our exploitation… Let’s get organised in working-class areas – rip up the gas, electricity and phone bills. Tear up the rent book. Don’t pay for public transport anymore! Let’s take all we need, let’s reappropriate our lives!” (Behan, 2000, p. 89)

These words from the leaflet were being repeated only a week earlier, because Dario Fo’s Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay! had premiered at the Palazzina Liberty theatre. It is a political farce in which working-class women, exasperated by soaring prices, refuse to pay for goods in the market, setting off a chain of comic and absurd situations. The play unfolds through the characters of two housewives, Antonia and Margherita, their husbands Giovanni and Luigi, and the looming presence of the police. Though the characters are initially caught in the dilemma between obeying the law and resisting it, they ultimately come to realize that resistance against the injustices of the state and the market is the only possible path. Through laughter, the play brings to light the oppression of the ruling class, the misery of the working class, and the resilience of ordinary people. In the charged atmosphere of the city, many feared that Fo and his partner Rame could be arrested at any moment, a narrative further amplified by the right-wing press. Even though they were not arrested, the state and right-wing forces continued to attack them in different ways for years to come. In the years that followed, the play travelled beyond Italy’s borders, becoming a powerful slogan for the anti-Thatcher movement in England.

In the present context of West Bengal, my adaptation of the play under the title Tras Capital – Mulyo Dhore Deben (“Terror Capital – Fix the Prices”), is not an attempt to draw a conscious parallel between every historical event and political condition across two distinct contexts and timelines. I began working on it in the winter of 2022, when relentless price hikes and unemployment with hundreds jobless people protesting on the streets of the city against corruption, had become a permanent condition in West Bengal, following the pandemic (Dey, 2021). Earlier, in 2019, I had adapted Fo’s One Was Nude and One Wore Tails into Ulonga Proja Porihito Raja (“The Naked Subject, the Attired King”), primarily as a response to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s second victory in the General Elections. The impact of that victory was felt acutely in West Bengal, where, following the end of thirty-four years of Left Front rule in 2011, far-right and centre-right forces had begun to dominate the political sphere. It was in this context that Fo’s farcical lens once again appeared both relevant and compelling to me.

I argue that the decline of the Left in Bengal and the decline of the Bengali Group Theatre Movement is symptomatic of one another. During the thirty-four years of Left Front rule, there was a gradual consolidation of the middle class within the party leadership. Similarly, renowned “progressive” theatre groups withdrew from their commitment to revolutionary theater, opting instead for a compromise with the government for vested interests. This is what I call the bourgeoisification of the Bengali Left, where the class struggle gradually receded from the movement and the stage. By the end of the Left regime, the combined pressures of neoliberalism and the escalating centre-right and right-wing opposition made it easy for these groups to be co-opted. Following the change of government, many of the same cultural figures and theatre personalities continued to comfortably occupy positions of authority. The bourgeoisification of Bengali theatre, and of art and culture at large, has become an almost irreversible phenomenon, one that perhaps only a mass people’s theatre movement could disrupt, even if for a fleeting moment.

Stages of Bourgeoisification: Theatre, Populism, and the Left

The Bengali Group Theatre, of which I am a part, traces its roots back to the colonial period, when the proscenium stage, Western architectural forms, and theatrical conventions were first introduced in Calcutta. The Bengali urban middle class emulated the colonizers to create indigenous theatre companies modeled on European-style theatres. Since that period, Calcutta has been the epicentre of Bengali theatre, a position it still holds today. The entire scenario of Calcutta-based theatre changed with the inception of revolutionary theatre through IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association), the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India, which carried its project throughout the country during the 1930s and 1940s. The Bengali theatre became a vehicle for expressing the angst generated by the Second World War and the devastating famine of 1943-44, and was now situated as a component of civil society, a space in which political battles were reflected. However, the pioneering role of IPTA was short-lived, for manifold reasons: the party was declared illegal, and dissensions grew between artists and the party. Gradually, thespians started leaving IPTA and formed theatre groups of their own, paving the way for the New Theatre Movement (Nabanatya Andolan), the so-called progressive theatre of the city, led mainly by the urban educated middle-class intelligentsia, of which this play and my group is also a part. Nevertheless, the Group Theatre movement, since its inception, was driven mainly by left-democratic ideals. But gradually, these groups and the movement became more and more Calcutta-centric, and their language, form, and aesthetics drifted far away from the working class and from the rest of the state. The fall of the Group Theatre Movement somehow parallels the fall of the Left in West Bengal.

The working class in the old sense disappeared. Two major political developments lie behind this: first, the blurring of class inequalities from cultural rhetoric and ethos; second, the replacement of the concept of class by ‘the people’. Though this shift started in American and European societies with the apparent vanishing of the industrial working class, it deeply influenced the Bengali middle-class intelligentsia. The antagonists were no longer labour versus capital, the working class versus the capitalists, but ‘the people’ versus a tiny band of super-wealthy tycoons, “the enemies of the people” (Chatterjee, 2024, p. xvii). The urban educated middle-class leadership of the Group Theatre movement directly reflects the contemporary leftist formations of this state, paving the way for populism, and as a result, they themselves lost their connection with the masses. For such a populist notion only produces a certain kind of solidarity based on concessions and negotiations with the elite to lessen the hardship of the so-called ordinary people. That is why most movements here end in negotiations and settlements, without any prolonged struggle or mass mobilization. This process of transformation within the Bengali Group Theatre and the Bengal Left is, in this case, bourgeoisification. Having situated the broader socio-political context and the historical lineage of both Dario Fo’s farce and the shifting trajectory of Bengali group theatre, I now turn to my own adaptation as a case study. Tras Capital – Mulyo Dhore Deben becomes a lens through which these questions of bourgeoisification, neoliberal restructuring, and the decline of Left cultural praxis can be examined in practice. By analysing the adaptation’s themes, dramaturgy, and performative strategies, I seek to show how theatre today negotiates its relationship with both the working classes and the urban middle-class audience.

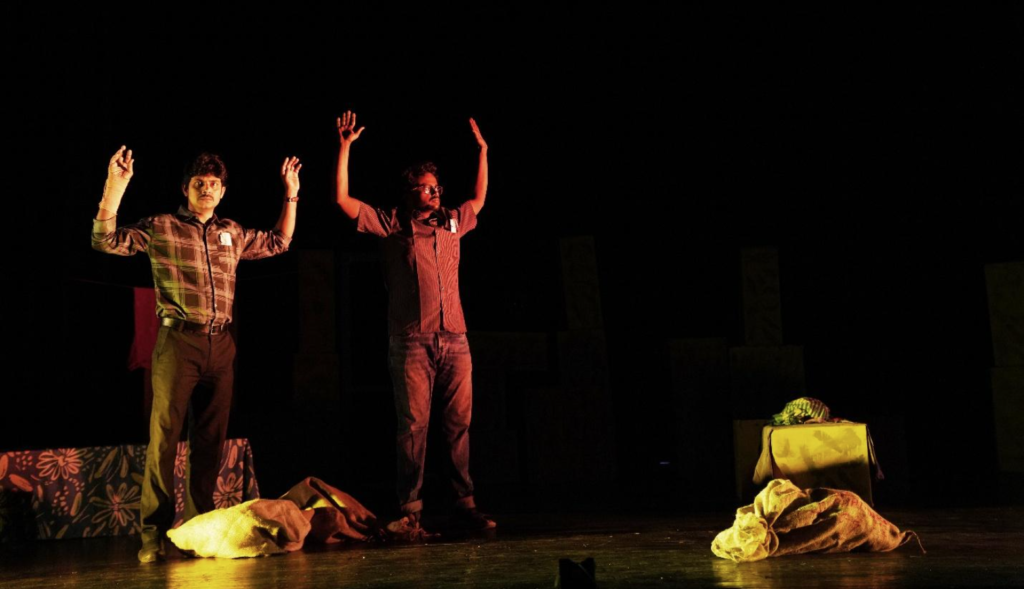

Image ‘Inspector: I can see everything! Jai Sati Mata! Jai Bajrangbali! Jai Shri Ram! What is this – am I carrying a child in my womb too?’ by Suddhayan Chatterjee (2025) is from the premiere of Tras Capital – Mulyo Dhore Deben.

Markets in Crisis: Adaptation and Agrarian Precarity

Fo’s 1974 Italy saw the Hot Autumn (1969), where factory workers launched strikes and shutdowns. They embraced “autoriduzione” (auto-reduction), refusing to pay inflated prices and demanding fair prices (Ginsborg, 2003, p. 359). Unlike in Italy, the concept of large departmental stores is not common in Calcutta. Instead, there are shopping malls and city marts, concentrated mainly in urban areas. These city marts are often strategically placed near local markets to attract consumers with multiple offers and discounts that local vendors cannot match. The characters are situated in the southern part of the city, a significant site of refugee origins and settlement after the Partition. [1] Fo’s Giovanni and Luigi are reimagined as Abhi and Manoj, who live in the same rented complex with their wives. Both of them are IT employees working in the BPO sector stationed in the Salt Lake region. I identified with Abhi and the dichotomy he inhabits, infusing his character with certain alienating scholarly mannerisms. In conversations with his wife, fragments of this conflict surface, positioning him at the centre of a clash of values between her and his friend Manoj. Manoj is a carefree individual, a rebel of sorts without clear political direction, unconcerned with the moral universe that constantly pesters Abhi from within. Their wives, Jhuma and Piyali, bear the weight of their husbands’ precarious employment, with temporary contracts and rotational shifts, straining their roles as homemakers. The script was initially aimed at the intrusion of industrialists and their monopolization of markets, with discontented people looting retail stores after a visit to the market. [2]

In the revised script, the loot is triggered by the words of a farmer leader addressing the people around in front of such a city mart. The leader explains that the goods flooding these stores are from cultivators trapped in contract farming, where corporations backed by state policy bought produce at coercively low prices. Due to inaccessible and ineffective cooperatives, farmers are pushed into these contracts, which promise security at the price of their bargaining power (Nandi, 2023). Meanwhile, the government and media frame middlemen as the culprits behind rising prices, obscuring the deeper nexus between corporate capital and state policy. The leader’s speech explicates how these malls and marts are responsible for farmers’ dispossession, the collapse of local markets and the ruin of small traders (Dey, 2014). At this point, the women erupt, turning grievance into collective reclamation that sweeps through the city. This shift makes it possible to link scarcity and inflation to the larger restructuring of agrarian policy, where contract farming serves corporate monopoly at the cost of local economies. Following Fo’s farcical mode, my adaptation lays bare how the market system inflates prices to the benefit of industrialists.

Beyond mocking and critiquing age-old theatrical conventions, techniques and acting mannerisms that persist even today through the performance, the play uses soundtrack from Anurag Kashyap’s film Gangs of Wasseypur (2012), called Kehke Loonga (Will Reclaim it Openly) in a chase sequence where Abhi and Manoj suddenly find sacks of rice and flour that, as if emerging from the darkness, spilled from a truck that has crashed nearby. The police inspector enters the scene as Manoj tries to make Abhi understand the present scenario. Their conversation, followed by a chase sequence under flickering lights, attempts to create a slow-motion cinematic visual in the musical rhythm. Together, these elements work on multiple registers. Abhi voices the exhaustion of the salaried middle-class, expressing the impact of years of stagnant or falling wages, the sense that “this job won’t last long,” and the humiliation of being unable to afford basic rations. On the other hand, Manoj provides the ideological rupture by insisting that hunger has made legality meaningless. He claims, the ‘theft’ of the sacks lying there, abandoned in the rain is survival and even justice.

Abhi: Ugh! I will not steal. I won’t even touch anything that doesn’t belong to me.

Manoj: What doesn’t belong to you? What doesn’t belong to me? What theft are you talking about! Don’t you pay taxes?

Abhi: Of course, I do. Why wouldn’t I?

Manoj: And with that tax money, all the MLAs and MPs ride around in air-conditioned cars, fly abroad in airplanes, pocket lakhs of rupees every month – and God knows what else! Yet in your own house you can’t even afford to keep the stove burning twice a day. How does it feel, hearing the truth?

Abhi: I understand. But this has been going on for years. All by the rules. This can’t be changed overnight!

Manoj: Then how will it change? When will it change?

Abhi: We need to act lawfully. What you’re suggesting would throw the whole country into chaos. In fact, it has already begun. This morning itself, from the office canteen to the local supermarket, people barged in and looted! By tomorrow morning we’ll know how many more places this has spread to. If this continues, the state won’t stay silent!

Manoj: What will it do? The police are right around the corner. They’ll call in the army. Then they’ll declare an emergency. And after that, they’ll unleash their repression. But even then, people cannot be stopped.

Abhi: What are you doing, brother! Don’t talk like this here! We’ll land in trouble. Our country is the world’s largest democracy! Don’t say such extremist things.

Manoj: Ha! You sound just like one of those News Anchors of “Republic Now”! Speak the truth and you’re branded extremist! If this is such a democracy, then that means the people who voted these leaders into power are either just like them or at least their collaborators. Do you really think all the looting that happened across the city today – who organized it?

Abhi: Surely, someone must be behind it.

Manoj: No, my friend! It was ordinary people like you and me. Breaking every protocol and procedure, common people have now taken to the streets. Well… what’s the point of saying more?

The conversation is placed in the rain-soaked chaos of a crash site and punctuated by the soundtrack of vengeance. This produces a quivering visual rhythm that culminates in the chase choreography, where the inspector pursues the two fugitives. The sequence intensifies as the ensemble joins in a frenetic game of toss and catch, repeatedly fooling the inspector. Through this scene, the play seeks to invoke the moment of the inevitability of rebellion, during the Milan uprisings of 1974. The provocation is not just to Abhi but to the audience: if the “largest democracy in the world” cannot feed its citizens, then what is left to reclaim but survival itself? Moreover, this sequence also exposes how Abhi’s understanding obscures the fundamental economic and political reality, where the intelligent man is driven through unemployment into a profession he despises. So, altogether, this sequence is an indictment of the failures of representative democracy under neoliberal capitalism.

Monoj: What! You’ll lose your honour if you steal! / Abhi: What stealing! That’s my own stuff. Give it… Image by Suddhayan Chatterjee (2025) is from the premiere of Tras Capital – Mulyo Dhore Deben.

In one of the most subversive sequences, the police inspector finally apprehends Jhuma and Piyali in Jhuma’s apartment while they attempt to conceal the looted provisions by stuffing them into their garments, pretending to be pregnant since earlier that day. When confronted, they defiantly warn the inspector that their condition is real, attributing it to the boon of the Sati Mother Goddess, whose vrat (ritual vow) they had observed to be blessed with sons like Lord Rama. This performative act is framed against the contemporary political discourse of Ramrajya (The Kingdom of Lord Rama), under the NDA government led by the BJP, whose ideological project seeks to establish India as a Hindu Rashtra, an exclusive state that privileges Hindu majoritarianism while marginalizing minorities, particularly Muslims. When the inspector remains unconvinced, the women begin reciting an invocation of Goddess Sati Ahalya, a mythical character from the epic, performing it as a ritual chant. The text of this prayer, composed by Debayudh Chatterjee, utilizes the metric configuration of the Panchali, a narrative folk song rooted in premodern Bengali poetry, to extend its scope beyond mythic reference and address the contradictions of contemporary Indian society. Performed with folk instruments, the panchali explicates the paradox of a culture that, on one hand, worships goddesses and, on the other, continues to inflict systemic violence on women, alluding directly to a notorious recent case of gang rape and murder in the city. [3] The poem also questions the complicity of the judiciary, critiquing it for absolving perpetrators due to legal loopholes and the so-called “lack of substantial evidence.” The composition takes the shape of a mock epic, drawing on the farcical modes described in the Natyashastra to situate the women’s act of defiance within a tradition that exposes the grotesque incongruities between divine ideals and lived realities.

The Digital Siege: Scenography, Media, and Global Dispossession

The scenographic design of the play is entirely constructed of disposable and discarded materials. Packing boxes layered with painted tissue paper are used to evoke the damp and shabby interiors of a lower-middle-class household. Apart from that, the depth of the stage is cluttered with thermocol slabs, snaking wires, and dysfunctional electronic devices such as old telephone receivers, broadband routers, and modems sourced from scrap dealers. Wires stretch across the stage from wing to wing, evoking the suffocating mesh of cables that dominate the urban skyline, running from poles to terraces and from high-rise apartments to slums. This creates a claustrophobic visual environment and a constricted sky. Two windows are placed symmetrically at the stage edges and function as the central dramaturgical devices. The first, open, becomes the site of performer entrances, symbolically staging contradiction. It points toward the persistent schisms within leftist organizations in India that prevent the formation of a unified front. The state exploits this very contradiction, with the police using the same window to barge in and curb down dissent. The second window takes the form of a vertical screen designed to resemble a smartphone interface. Through this screen, the act of doom-scrolling is staged. The play begins with projections on this surface, initially showing viral humorous reels before abruptly shifting to distressing political imagery. This includes Israel’s relentless bombardment of Palestine, the Pahalgam terror attacks, the unfolding crises in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the United States, as well as scenes from African countries depicting desperate acts of looting in shopping malls and departmental stores. These sequences are interspersed with excerpts from Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away!, a British reality television documentary series that situates the local narrative of economic struggle within a broader global context of dispossession and systemic collapse.

In extending the central narrative, I introduced additional characters who are represented as PUBG players. They suddenly enter Abhi’s apartment, their arrival marked by the recognizable game sound “I got supplies.” Their entry is abrupt and disruptive. They forage beneath the bed to find food packets before disappearing as abruptly as they arrived. Later, when Abhi and Manoj leave in search of their wives, these players reappear, armed with toy guns and caught within the logic of digital combat. They are soon ambushed by unseen opponents. At this moment the screen projects a visualization of the game, announcing the interval between the two acts with the unsettling message “We’ll be back after the genocide,” followed by the correction “after ten minutes.” The interval is then accompanied by Anthony Warlow’s 1995 song It’s a Dangerous Game.

The use of these PUBG players is inspired by HADO, a recent Japanese augmented reality e-sport described as the world’s first of its kind. In HADO, players wear visors and wrist sensors to launch virtual energy blasts while moving in a real-world arena. This game emphasizes physical agility, coordination, and tactical awareness over the common handheld controller experience. My theatrical attempt seeks to subvert the promise of AR gameplay, where instead of liberation and the joy of embodied play, the players become trapped, overwhelmed by invisible forces that allegorize how the neo-imperialist powers repress liberation movements. The use of projection here on the screen translates the game’s immersive world into stage terms, and the border between game and brutality collapses. The music heightens this collapse. The soundscape is composed largely of electronic noise fused with rhythmic pulses that evoke the urgency of gaming environments. The layering of artificial electronic sounds with structured rhythm produces a fractured auditory space, one that mirrors the unstable and threatening atmosphere of political violence. By blending the digital and the corporeal, the sonic design refuses to remain in the background, and it becomes an active participant in creating a sense of siege.

Conclusion

My adaptation stands as both a product of bourgeoisification and an effort to move away from it. Proscenium theatre’s reliance on state and middle-class patronage already situates the work within that logic, further marked by my shift of Fo’s working-class characters into urban middle-class figures. Yet the play also resists these confines by reworking form. It uses farce to expose present political realities, music and choreography to stage collective struggle, and new media to engage with a new century and a new audience. Analysing the adaptation as a case study shows how bourgeoisification distorts practice, while practitioners struggle against its pressures to generate possibilities of resistance. At the same time, the erosion of collective theatre practices marks another facet of this process. Since the collective was no more, theatre groups became led by individuals, families, or legacies, where creative scope and freedom are restricted. Such individualistic endeavours opened the path to identity politics in the globalized economy, where neoliberalism plays its double game between identity and difference. Thus, the very groups that once performed for the Left Front in election campaigns changed camps, later promoting the opposition, and after the power shift, again received the same benefits they once enjoyed. In this way, bourgeoisification still functions, deeply interpellated within us.

The revolutionary fervour of Bengali theatre has disappeared. It has now shifted towards mythic or epic narratives, prosaic adaptations, or eclectic avant-garde forms that have no real connection with the masses. Moreover, many of these productions are funded by the government itself, allowing them to be censored in numerous ways. This mirrors the situation of the Bengal Left. Over time, the Bengal Left confirmed its approach of being “politically correct” in response to every incident, and because of its middle-class leadership, it failed to launch a proper movement against the establishment. In contrast, the Left across India has re-emerged in new and united forms, from Maharashtra to Rajasthan to Tamil Nadu. It is especially noteworthy how the Left in Tamil Nadu and other southern states has consolidated unions for gig workers and corporate employees. While such efforts exist in Bengal as well, they are far less palpable and visible than in the aforementioned states.

It is precisely at this point that I want to intervene through this adaptation. This is not the time for political correctness. The Left must continually seek movements and insurgencies and work toward constituting a larger rebellion against the state. Yet bourgeoisification has brought us to a situation where, no matter how radical the dialogues I write or how much of reality I expose, at the end of the day, my theatre caters to the bourgeoisie and the urban educated middle class. They are the ones who will buy my tickets, or the government will provide funding. For practitioners, it has become nearly impossible to leave the eclectic confines of proscenium theatre. Regardless of financial constraints, in our attempt to reach the working-class audience, we practitioners drifted long ago from their language, forms, and aesthetics. The only way forward is for performance itself to undo “theatre.” It must interact with new media and other modes of communication to engage the new working class. This is why I decided to introduce the vertical screen on stage with a strong visual presence. The Left of the new century has to redefine theatre in order to revive the moment of reclamation.

Acknowledgement

I thank thespian Bratya Basu, my mentor, Abhijit Roy, my PhD supervisor, and Debayudh Chatterjee, my teacher, researcher, and poet, for constantly provoking me to think.

Notes

- “Partition” here refers to the division of British India in 1947 into India and Pakistan, which led to the creation of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and the partition of Bengal. In West Bengal, the event was marked not only by mass displacement and communal violence but also by a long history of refugee rehabilitation and social dislocation in border districts. The effects of Partition continue to shape everyday life in these regions, where displaced and marginalized communities are still vulnerable to state surveillance and exclusion, a situation intensified under the BJP-led NDA government’s implementation of the NRC and the CAA.

- Abhijit Roy, my PhD supervisor, suggested that I shift the focus towards contract farming and its consequences in West Bengal.

- The Hathras case (2020) involved the gang rape and murder of a 19-year-old Dalit woman in Uttar Pradesh, sparking nationwide outrage over caste-based violence and mishandling by authorities, including the alleged forced cremation of the victim’s body without family consent. The RG Kar incident (2024) refers to the rape and murder of a 31-year-old postgraduate trainee doctor at Kolkata’s RG Kar Medical College and Hospital, leading to widespread protests and a CBI investigation, monitored by the Supreme Court of India.

References:

Behan, T. (2000). Dario Fo: Revolutionary theatre. Pluto Press.

Chatterjee, P. (2024). Foreword. In B. Dutt & S. Jestrovic (Eds.), Theatre, activism, subjectivity: Searching for the Left in a fragmented world (pp. xv–xix). Manchester University Press.

Dey, B. (2014, September 29). পূরণ হয়নি ধান কেনার লক্ষ্যমাত্রা, ক্ষোভ [The target for paddy procurement has not been met, frustration]. Anandabazar Patrika. https://www.anandabazar.com/west-bengal/midnapore/%E0%A6%AA-%E0%A6%B0%E0%A6%A3-%E0%A6%B9%E0%A7%9F%E0%A6%A8-%E0%A6%A7-%E0%A6%A8-%E0%A6%95-%E0%A6%A8-%E0%A6%B0-%E0%A6%B2%E0%A6%95-%E0%A6%B7-%E0%A6%AF%E0%A6%AE-%E0%A6%A4-%E0%A6%B0-%E0%A6%95-%E0%A6%B7-%E0%A6%AD-1.73686

Dey, S. (2021, November 25). What is SSC scam? Latest ‘CBI headache’ for Mamata govt despite 3-week relief from HC. The Print. https://theprint.in/theprint-essential/what-is-ssc-scam-latest-cbi-headache-for-mamata-govt-despite-3-week-relief-from-hc/771352/

Ginsborg, P. (2003). A history of contemporary Italy: Society and politics, 1943–1988. Palgrave Macmillan.

Nandi, P. (2023, December 15). কৃষি সমবায়ে ভরসা হারাচ্ছেন বহু চাষি [Farmers losing trust over agriculture cooperatives]. Anandabazar Patrika. https://www.anandabazar.com/west-bengal/howrah-hooghly/farmers-losing-trust-over-agriculture-cooperatives-at-arambagh/cid/1481626