Colonial Soldiers and the Epistemic Injustice: The Case of Chien Mao-Sung

Article by Ellen Lin

Abstract:

This article examines the war crimes trial of Taiwanese colonial soldier Chien Mao-Sung to explore how colonial subjects were structurally silenced in the postwar justice system. Mobilized under imperial rule and later tried as a Japanese soldier, Chien’s experience was reduced to personal misconduct. By comparing his testimony with tribunal records, this article argues that his position exemplifies what Miranda Fricker calls hermeneutical injustice—when one’s experience cannot be intelligibly expressed—and what Judith Butler theorizes as ungrievability—when a life falls outside normative frames of recognition. The trials did not merely overlook colonial violence; it actively erased it through legal and linguistic structures.

Keywords: epistemic injustice, ungrievability, colonial soldiers, postwar trials, Taiwanese Japanese Soldiers

Header image “Australian War Memorial” by photographer staff sergeant R.L. Stewart is licensed under public domain.

Introduction

This article is adapted and revised from my MA thesis, Epistemic Injustice and Taiwanese Japanese Soldiers: The Case of Chien Mao-Sung. It examines the case of Chien Mao-Sung, a colonial man under Japanese Empire colonial rule, and analyzes how his postwar trial experience was shaped by both linguistic and epistemic ruptures. During the war, Chien was recruited as a civilian employee and assigned to guard Allied prisoners of war (POWs). However, after the war, he was tried and sentenced to five years in prison as a “Japanese soldier.” His flesh became the visible target of colonial violence and was punished accordingly—yet the fact that it was a colonized body remained unrecognized and unnamed.

This article draws on Miranda Fricker’s (2007) concept of hermeneutical injustice and Judith Butler’s idea of ungrievability (2016) to examine how knowledge and recognition are shaped. It asks: when a group’s experience lacks the words to be properly understood, can their lives still be seen as lives worth mourning? More importantly, this article does not only focus on who was convicted in postwar trials, but also on who was allowed to speak, whose experiences became valid testimony, and whose stories were silenced by the system.

Analysis of Chien Mao-Sung’s Autobiographical Testimony

Chien Mao-Sung was born in colonial Taiwan under Japanese Empire rule. During the war, he was conscripted as a civilian employee and dispatched to a prisoner-of-war camp in Borneo to guard Allied captives. According to his autobiographical account, in 1945, he and other colonial youths from Taiwan were spot conscripted as regular soldiers. [1] (Hamazaki/Chien, 2001) After the war, he was convicted by an Australian military tribunal for “mistreatment of prisoners of war” and sentenced to five years in prison. He argues that he could not defend himself well due to the barrier of language. Upon completing his sentence, he was denied reentry into Japan by the Japanese government—deemed a “foreigner” due to his war criminal status and Taiwanese origin—and was forced to survive on his own in Japan. In examining the post-war trials, I compare Chien Mao-Sung’s oral testimony with available historical records. The analysis reveals significant differences between Chien’s statements and those of other prisoners of war. However, based on the existing documents alone, it is difficult to determine the truthfulness of either side. This article aims to highlight the plurality of historical interpretations and to create space for deeper reflection, in order to more comprehensively understand the value and implications of Chien’s testimony within the broader discussion. I contend that history is not a singular, linear narrative; it can take the form of an official version fixed by archival authority, or circulate as individual memories passed down informally. More often, however, history is told in specific ways—like viewing the past through a lens that draws attention to certain aspects while obscuring others. I believe the key question in historical inquiry is not merely one of truth or falsehood, but to figure out why these histories are told in this way. The aim of this chapter is to examine the complexities of the post-war trials and to clarify the role that Taiwanese Japanese soldiers played within this context.

In the book, Chien emphasizes that he was sentenced to five years in prison for a single slap. He expressed strong dissatisfaction and confusion about this outcome. He pointed out that the entire trial process was rushed and that he could barely understand what was happening. He wrote:

The result of the judgment was that I was sentenced to five years, one year less than the prosecution had sought. The sentences were handed down one after another, each person spending less than five minutes before being hurried out of the tent. Honestly, we were condemned as criminals without fully understanding the situation. While many Taiwanese were acquitted, I was sentenced to five years for slapping a prisoner twice—a sentence that could cost me my life. Furthermore, it seemed that being promoted from military attaché to a full soldier had damaged the Australians’ impression of me, as all six of us who were drafted were found guilty without exception.

Since I always believed I was innocent, it was hard to accept that a five-year sentence was the price I paid for two slaps that were as insignificant as a mosquito bite compared to the punches and slaps my Japanese superiors inflicted on prisoners. The rumor among my comrades that ‘one slap means five years, and one punch means ten years’ came true. (Hamazaki/Chien, 2001, p. 94-6)

For Chien, the two slaps were not just isolated acts of violence, but a continuation and reproduction of the broader culture of violence within the military. He emphasized that he carried out the slapping under orders from his superiors, not because of any personal tendency toward violence. He recalled:

I never acted violently toward prisoners because I have always despised brutality. However, I did slap a prisoner once.

I was on duty at the front gate when a British colonel passed by without saluting me. The colonel was tall, bearded, and always carried a baton under his arm like British officers do, strutting past without ever saluting me on guard.

I decided to let it slide, thinking it was good to allow them some dignity. But, as luck would have it, a petty army sergeant happened to pass by on a bicycle and questioned me. The sergeant then chased after the colonel and dragged him back to me.

“Are you blind? You just let him swagger past without saluting! This is outright disrespect to the Japanese military!”

I didn’t want to slap him, so I hesitated. Seeing this, the sergeant snarled, “Hit him now! That’s an order!” Reluctantly, I held the towering colonel and lightly slapped his left cheek.

“What are you doing? Hit him again, harder this time!” the sergeant barked, so I tried to slap harder and louder.

That was the only time I ever assaulted a prisoner, but the angry, humiliated expression on that British officer’s face remains deeply etched in my mind. (Hamazaki/Chien, 2001, p. 59-60)

Chien also mentioned that he was often beaten and humiliated by his Japanese superiors during military service. For example, during a training session, he was pushed down a slope, and a wooden bayonet pierced his mouth, causing him to lose his front teeth. He described this violent culture as a top-down system of imitation, and stated: “The Japanese military’s ‘slap culture’ was the main culprit behind the large number of Taiwanese B/C war criminals [2], but that’s a story for later” (p.56). He believed that the normalization of such institutionalized violence led many Taiwanese Japanese soldiers to participate in violent acts without full awareness, which later resulted in them being accused as war criminals.

From this, we can see that one of Chien Mao-Sung’s main grievances was that his actions were coerced, and the punishment he received did not match the nature of the offense. A review of historical records shows that there are only a few documents available related to Chien Mao-Sung’s trial.

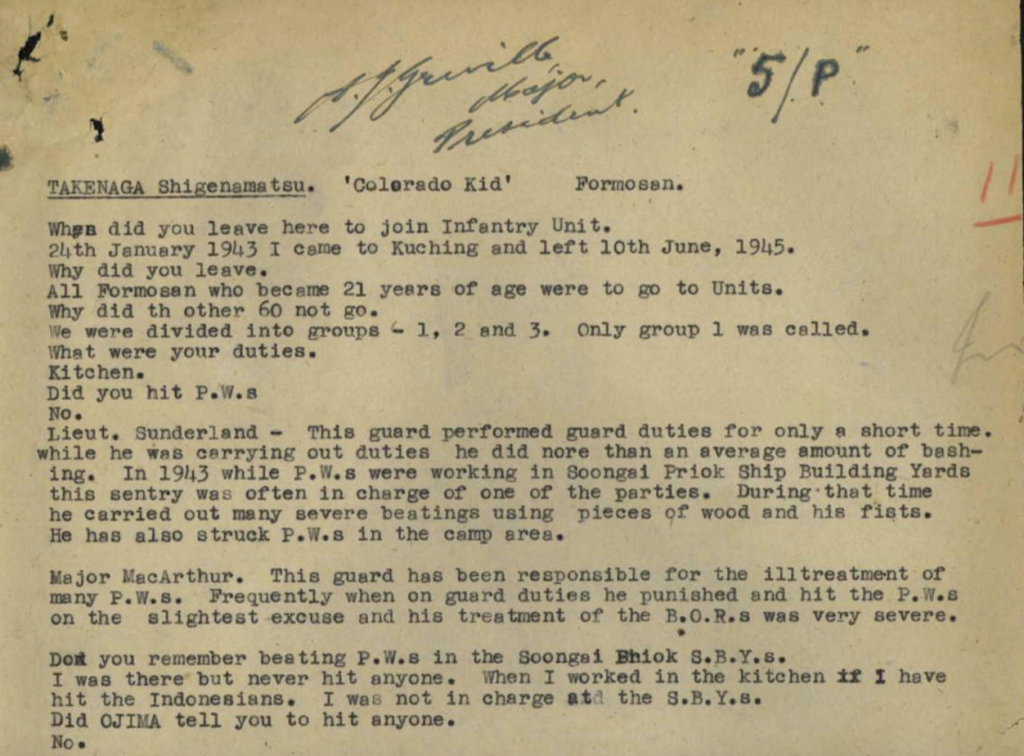

Image: “NAA: A471, 80754 PART 3, p. 166” Australian war crimes tribunal record, Morotai trial on the Kuching (Sarawak) POW camp, January 1946.

Excerpt from the National Archives of Australia (NAA: A471, 80754 PART 3, p. 166). This publicly available document refers to “TAKENAGA Shigenamatsu,” the Japanese name of Chien Mao-Sung (written as 簡茂松 in Chinese and 竹永茂松 in Japanese kanji). [3]

The document indicates that Chien was accused of beating prisoners with sticks and fists. This account contradicts Chien’s own testimony, and the actual circumstances remain uncertain. However, I must note that while I am not inclined to accuse Chien of lying, I am also not in a position to question the testimonies of the prisoners at the time. That said, compared to others tried in the post-war tribunals in the Kuching area, Chien received a relatively light sentence.

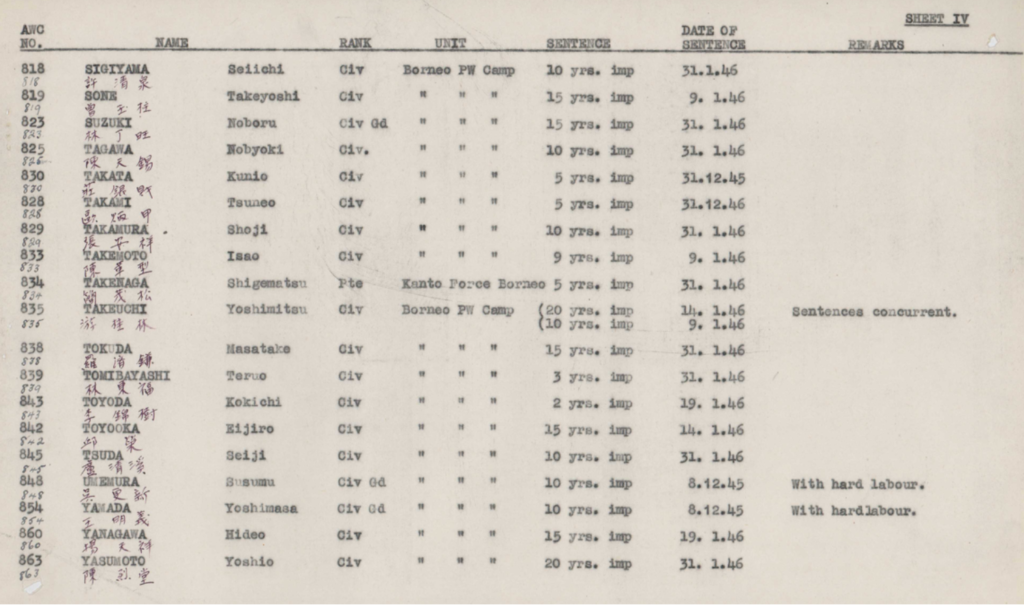

Image: “AWM54 1010/2/38, p.10” Australian War Memorial archival file from the Second World War and war crimes trial records series.

As shown in this document (AWM54 1010/2/38, p.10), Chien, listed as number 834, received a sentence that was relatively light compared to the majority of other cases, which ranged from 10 to 20 years. The rest of the list of convicted war criminals is omitted here for brevity.

In addition to his frustration over being punished for carrying out violence under orders, Chien also complained that the interrogators failed to understand the difference between volunteering to serve and being spot conscripted.

In early December, the Australian military tribunal commenced in Labuan. Prior to this, we were summoned one by one for questioning. I thought this was merely an initial gathering of evidence based on the accusations from former prisoners, but the interpreter’s poor command of Japanese led to confusion about the details.

One particular interrogation that I clearly remember was: “You are Taiwanese, yet you voluntarily became a Japanese soldier to kill us.” I responded, “With Taiwan issuing a conscription order, I was conscripted on the spot; I did not enlist voluntarily.”

However, it seemed that the interpreter either did not understand the terms “conscription order” and “spot conscription,” or pretended not to. As I recall, he did not accurately translate my statement. He even accused me, saying: “You abused an English Colonel (I cannot recall the name, just that he was a large man who refused to salute) — this is clearly mistreatment of prisoners!” (Hamazaki/Chien,2001, p. 90)

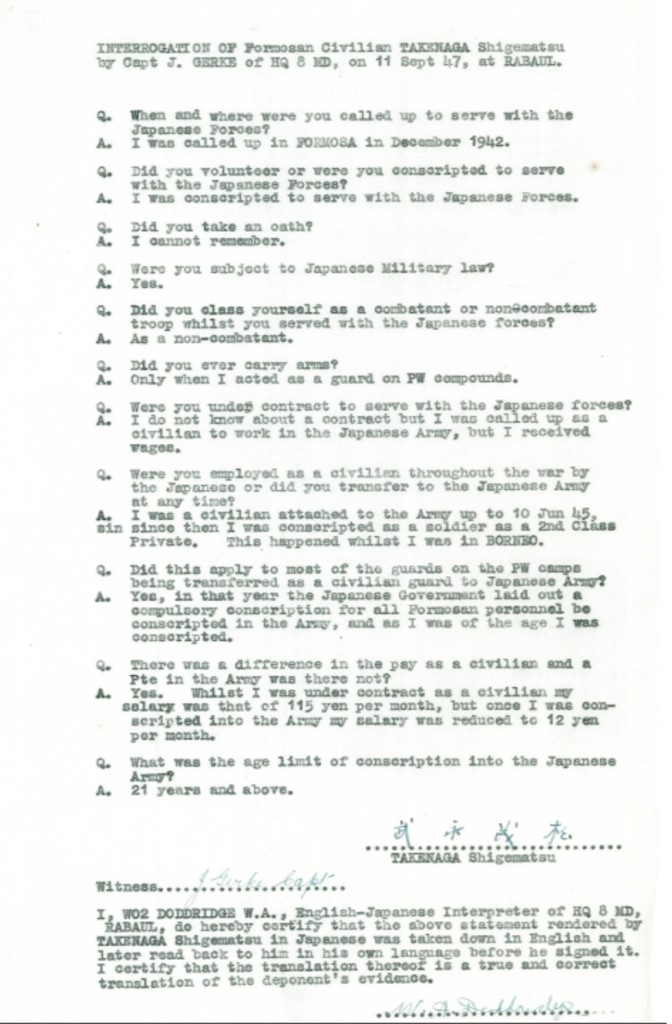

For clarification, Japan implemented two types of conscription systems in Taiwan. One was the Army Special Volunteer System, which began in 1942, and the other was the conscription system introduced in 1944. The Special Volunteer System continued even after the conscription system was introduced. When Chien became a civilian employee in 1942, he was recruited under the volunteer system. Later, in 1943, he was deployed to Borneo and Kuching as a guard at a prisoner war camp. When the conscription system was enacted in 1944, Chien was locally conscripted as a “soldier” rather than a civilian employee. If this explanation of the distinction between “conscription order” and “spot conscription” is unclear, consider it as a form of unpursued promotion: he transitioned from a logistical auxiliary role to a frontline soldier, but this change occurred without his consent, which is the point he was trying to make in the following quote. In the historical document AWM54 1010/2/38, we can read about the process in which Chien was interrogated on this matter. See the following picture.

Image: “AWM54 1010/2/38, p.5” Australian War Memorial archival file from the Second World War and war crimes trial records series.

In this process, Chien Mao-Sung tried to explain the difference between soldiers and civilian employees, but it is unclear whether he succeeded. In his book, Chien complained that the translator was not attentive enough and failed to accurately convey his statements, which led to a harsher sentence due to a misunderstanding about his “voluntary enlistment.” This conversation indeed shows that he was initially a government employee and later enlisted because he met the requirements. However, in what Chien described as an “assembly-line” interrogation, it is doubtful whether these explanations were fully understood. As Dower (1999) puts it: “…. Although some suspects languished in their captors’ hands for several years before being brought to judgment, the trials, once convened, were generally swift. Despite language problems, they averaged around two days each….” (p. 448)

It is important to clarify that Chien’s dissatisfaction involved several key points. He argued that, as a civilian employee in the military, the tasks and equipment he received from the Japanese empire made it nearly impossible to distinguish him from a soldier based on appearance alone. He believed this visual confusion, combined with the top-down culture of violence, was intentional—designed to redirect the prisoners’ resentment toward Taiwanese guards, allowing Japanese soldiers to evade responsibility (p. 87). Moreover, he felt it was unfair to punish him as a soldier, since he had initially joined as a civilian employee and was later forced to become a soldier without having any choice or the ability to disobey. Finally, although he acknowledged that he had voluntarily become a civilian employee, he believed this “voluntary” enlistment was shaped by militarist indoctrination. He admitted that being punished for helping the Japanese military was understandable (p. 89), but insisted that it was unreasonable to impose a harsher sentence by insisting that he had voluntarily become a “soldier” rather than a civilian employee.

Based on the discussion above, I argue that Chien Mao-Sung experienced what Miranda Fricker calls hermeneutical injustice during his trial as a B/C-class war criminal in the Australian military court in 1945. Due to structural limitations of language and identity, his position as a colonial soldier could not be properly understood, leading to silencing and exclusion. He was sentenced to five years in prison for “two slaps” (Hamazaki/Chien, p. 94–96), actions rooted in the Japanese military’s culture of corporal punishment, yet simplified as personal wrongdoing.

A mistranslation of the term “spot conscription” prevented him from explaining the coercive nature of his military service, leaving him voiceless due to a lack of interpretive resources. The trial assumed he had the same autonomy as a Japanese soldier, ignoring the colonial oppression he had endured, resulting in a misrecognition of his status. The rapid trial process further limited any inquiry into his historical background, and the court lacked the language needed to address colonial experience, reducing his testimony to mere evidence of war crime.

Chien’s silencing exemplifies hermeneutical injustice. The historical silence surrounding colonialism marginalized his experience, revealing the exclusion of colonial soldiers from the framework of postwar justice.

Epistemic Vacuum of Colonial Soldiers

In the case of Chien Mao-Sung, we see a structural imbalance between language and power: he was not only forced to serve under the colonial system but was also unable to clearly explain the context of his actions during the trial due to mistranslation and misrecognition of his identity. This misrecognition was not simply procedural but ontological—it cast him as someone whose narrative could not even be formulated within the available terms of intelligibility. As Judith Butler (2004) argues, when a subject’s life cannot be framed within the normative grids of recognition, it becomes ungrievable, suspended outside the field of ethical response. According to Miranda Fricker, hermeneutical injustice refers to the situation where certain social groups occupy an unequal position within systems of knowledge production, leading to a lack of interpretive resources to express their experiences. When dominant discourses cannot accommodate these experiences, even when voiced, they cannot be properly understood or acknowledged.

The trial system assumed that Chien, like a Japanese soldier, could fully understand and follow military orders, but it ignored the multiple layers of subordination colonial soldiers faced—class, language, and race. These coercive conditions had no corresponding concepts within the legal framework. As a result, his testimony was reduced to evidence of “individual misconduct” rather than a reflection of the structural force he had endured.

The absence of colonial soldiers from the linguistic and ethical framework of postwar trials was not merely due to flaws in translation or legal procedures. It was deeply tied to how global power after the war reshaped the narrative structure of “justice.” The Tokyo Trial (1946–1948), as a symbolic performance of the postwar order, was not primarily aimed at pursuing responsibility across all levels of wartime conduct (Higurashi, 2017). Instead, it sought to reconstruct a “cooperative” image of Japan by individualizing guilt through the classification of Class A, B, and C war crimes. As Shibusawa (2006) points out, the U.S. employed gendered and infantilizing narrative strategies to portray Emperor Hirohito and the Japanese public as innocent victims misled by militarism. Only a small number of military leaders, such as Tōjō Hideki, were put on trial. This allowed for a moral separation and redistribution of war responsibility. This narrative became the ethical foundation for the postwar reconstruction of international alliances and established the criteria for who could be forgiven and who could be remembered. (Shibusawa, 2006, pp. 133–139)

The trials individualized war responsibility by reshaping Japan’s image through a binary framework of “good Japanese” (innocent civilians) versus “bad Japanese” (militarist leaders). Within this narrative, colonial soldiers like Chien were cast as unnecessary outsiders and hastily categorized as “war criminals.” His act of slapping a POW—rooted in the broader “slap culture” of the Japanese military—was reduced to a personal crime. The mistranslation of the conscription order prevented him from defending himself, exemplifying what Fricker calls hermeneutical injustice. Moreover, the very lack of linguistic resources that rendered his defense unintelligible stemmed from his position outside the framework of postwar order reconstruction—a form of ungrievability that denied him the right to be understood and mourned. Importantly, this absence of language was not a personal shortcoming but a political effect: the very framework of the postwar order actively excluded colonial experiences from its grammar of justice. In this sense, Chien’s inability to articulate his own position was not accidental but historically produced.

However, it would be inaccurate to say that Chien was entirely “unneeded” within the postwar structure. The U.S. occupation authorities in Japan promoted a narrative in which Japan’s defeat was attributed to militarist aggression. By publicly prosecuting a select group of military leaders, the trials served both as symbolic punishment and as a shaming spectacle meant to deter future militarist fantasies. This strategy aimed to weaken the cultural appeal of rearmament and implant a historical lesson— “aggression equals guilt”—into Japan’s collective memory. The trials thus functioned less as legal processes than as a means to install a particular historical narrative that would facilitate U.S.-Japan postwar cooperation. (Higurashi, 2017, p.4-46)

In this discursive framework, “Chien as a Japanese soldier” was incorporated as a negative example. Yet this form of justice was ultimately theatrical. If not, why was Chien’s experience of colonial violence—shaped by his status as a colonized subject—never treated as something that could be acknowledged or held to account?

Conclusion

Chien Mao-Sung’s experience cannot represent all Taiwanese Japanese soldiers. In fact, these soldiers encompassed a wide range of categories, with vastly different modes of mobilization and postwar fates. This article does not attempt to elaborate on those distinctions. My intention is not to claim that Chien is somehow representative, but rather to use this specific case to glimpse the broader institutional logics of colonial history and the postwar order as refracted through his linguistic experience.

Nor do I argue that Chien should be viewed simply as a victim. In my MA thesis, I have contended that the Japanese imperial policy of assimilation should not be understood merely as a one-sided imposition or deception, but rather as a performance involving complicity between empire and colony. Taiwanese Japanese soldiers were undoubtedly part of this structure. Some colonial subjects even enlisted to prove themselves as “real Japanese,” further complicating the ethical dimensions of this history.

However, in this article, I do not seek to judge the moral implications of Chien’s participation in war, nor do I present him as a figure of pity or redemption. What I wish to underscore is this: through the misrecognition of his identity and the mistranslation of his voice during the postwar trials, we can see how Taiwanese Japanese soldiers were both included in—and excluded from—the reconstruction of the postwar order.

Notes

- I refer to the source as “Hamazaki/Chien” to highlight that the book is an oral history based on Chien’s personal testimony, compiled by the Japanese journalist Hamazaki. This citation format is used for clarity, allowing readers to easily recognize that the narrative comes directly from Chien’s own account.

- In postwar tribunals, Taiwanese Japanese Soliers were prosecuted not as Class A “crimes against peace” defendants, but under Class B (violations of the laws of war) or Class C (crimes against humanity). Because many cases involved overlapping charges—such as the mistreatment of POWs (B) and inhumane treatment (C)—and the judgments often blurred the distinction, these defendants came to be collectively referred to as “B/C war criminals”.

- The nickname “Colerado Kid” was assigned to him by prisoners, who commonly gave guards such names due to not knowing their real identities. These nicknames are consistently used across trial documents to help investigators distinguish between the accused.

References:

Australian War Memorial. (n.d.). AWM54 1010/2/38 [Archival file]. Canberra, Australia.

National Archives of Australia. (n.d.). NAA471, 80754 Part 3 [Archival file]. Canberra, Australia.

Butler, J. (2016). Frames of war: When is life grievable? Verso.

Dower, J. W. (1999). Embracing defeat: Japan in the wake of World War II. W.W. Norton & Co.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Lin, S.-Y. (2025). Epistemic injustice and Taiwanese Japanese soldiers: The case of Chien Mao-Sung (Unpublished master’s thesis). National Central University, Department of English.

Hamazaki, K. (2001). I as a Japanese Soldier: Taiwanese Chien Mao-Sung’s “homeland.( 我啊!一個台灣人日本兵簡茂松的一生) (邱振瑞, Trans.). 圓神. (Original work published 2000 in Japanese)

Higurashi, Y.(日暮吉延). (2017). 東京審判 (THE Tokyo Trial) (Huang, Y.-C. & Hsiung, S.-W., Trans.). 八旗文化. (Original work published 2008 in Japanese)

Shibusawa, N. (2012). 美国的艺伎盟友──重新想像敌国日本 (America’s Geisha Ally) (牟學苑, Trans.; 2nd ed.). 江苏人民出版社. (Original work published 2010 in English)