Migration, Identity, and Digital Media: The Experience of Thai and Indonesian Migrants in Taiwan

Article by Pakorn Phalapong, Danny Widiatmo, Novita Siti Zubaedah, Pacharapol Katjinakul

Abstract:

The influx of Southeast Asian migrants in Taiwan and the ubiquity of digital media uses prompt this paper to explore how digital media uses of migrants shape their identity and belonging in the communities. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork in both physical and digital spaces, this report offers the experiences of Thai and Indonesian migrants in Taiwan. Thai migrants mainly utilized Line and TikTok to foster “virtual intimacy” by reciprocally circulating transnational care, virtual care, and workplace coordination. Indonesian migrants primarily leveraged WhatsApp for emotional co-presence, entrepreneurial coordination, and religious and ethnic solidarity. Digital media, hence, is not only a tool for communication but also an integral infrastructure for migrants’ emotional connections, community building, and diasporic solidarity in a transnational setting.

Keywords: migration, identity, digital media, Thailand, Indonesia, Taiwan

Header image “Digital media has an impact on the study of migration issues in many ways” by Indra Projects is licensed under Unsplash License.

Introduction

In recent decades, Taiwan has become a magnet for migrant workers across Southeast Asia seeking economic opportunities, especially in productive sectors. More than 100,000 are Indonesians and over 70,000 are Thais, making both nationalities the top sending countries by the end of 2024 (Ministry of Labor Statistics, 2024). Many leave their home countries due to limited economic opportunities in their countries and in Taiwan.

As much research has been published on their migration and social-welfare policies, only a few have focused on the other aspects, such as their cultural identity, which has always been one of the most important issues for Southeast Asian society, especially Indonesia and Thailand, which was constructed and influenced by the colonial history and the idea of nationalism (Anderson, 1983; Winichakul, 1994). Recently, digital media have also emerged as another aspect in migration studies, not only in the reformation of brokers-to-migrant relationships (Tajaroensuk, 2018; Soriano, 2021), but also in the construction of identity in a virtual space (Wallis, 2018). Given the identity construction process of the Indonesians and Thais, their experiences of migration and interaction with the recent digital media may represent a different experience and contribute to a new perspective in the study of migration. As more scientific investigation is needed to comprehend this understanding, this research questioned “how do digital media uses of migrants impact their identity and belonging in the communities?”

Image “Smartphones are not just communication tools, but relational infrastructures” by Lisanto 李奕良 is licensed under the Unsplash License

Research Framework

Identity and the circuit of inter-Asian mobility

Reflecting on Chen’s Asia as Method (2010), interactions, partnerships, and intellectual exchanges between Asian nations should be perceived as their merit. In a similar vein, Asian migrants in Asia should not be viewed solely through economic motivations, but also through a logic of culture that might influence the routes of mobility (Ong, 1999). Recent scholarship has offered examples including remittances as a form of cultural identity in performing migrants’ filial piety to their left-behind families (Sobieszczyk, 2015), ritualistic household practices from afar despite the absence of migrants’ presence (Cabalquinto, 2022), mobility as the never-ending and continuous process of identity formation as flexible citizenship or dual identity (Bauman, 2011), and mobility as a form of reshaping one’s sexuality and desirability (Yang, 2023). Building on this growing body of literature, this study endeavors to investigate the experiences of Southeast Asian migrants in Taiwan and their identity in light of their own Asian experiences, histories, and desires rather than as a reaction to or imitation of Western paradigms.

The utilization of digital technology in a migratory context

Digital technology has profoundly influenced various aspects of migrants’ experiences, identities, and interactions. It is an infrastructure that enables migrants to perform transnational care with their families and friends back home through instant messaging (Francisco-Menchavez, 2018; Cabalquinto, 2022). It offers access to a wealth of online information about their legal rights, facilitates migrants’ transnational networks, and promotes integration in host societies (Wilding, 2006). Moreover, it helps empower the migrants’ community (Wallis, 2018) and even reconfigures traditional roles of brokers by transforming them to be more functional (Soriano, 2021; Hoang, 2025). While the mainstream keeps the focal analysis on Filipino migrants’ digital uses (Francisco-Menchavez, 2018; Soriano, 2021; Cabalquinto, 2022), this study shifts attention to Thai and Indonesian migrants who constitute more than 20 percent of overall guest workers in Taiwan. Their engagement with digitality not only contests capitalist times (Fuchs, 2015) but also constructs their online communities and multifaceted expressions of identity.

Methodology

Ethnographic fieldwork is the main methodology of this research, including both actual and virtual spaces. Data was collected between 2024-2025. Details of the participants can be found on Table 1. Participatory observation, interview, focus group discussion, and digital ethnography were applied as data collection approaches. Inductive content analysis was used to underline a bottom-up explanation of migrants rather than having any presumption on their digital uses.

| Occupation | Number of informants | Ethnicity | Gender | Average age | Platform preference |

| Bar workers | 8 | Thai | Female | N/A | TikTok |

| Guest workers | 6 | Thai | Male | 34 | LINE |

| Small entrepreneurs | 3 | Indonesian | Female | 25 | |

| Small entrepreneurs | 7 | Chinese Indonesian | Female | 55 | WhatsApp

LINE |

| Total | 24 | – | – | 38 | – |

Table 1. Demographic of the participants

To follow ethical considerations, the interlocutors who had interviews were given informed consents prior to the interviews. Consent was given after the researchers explained research processes and relevant ethical considerations, followed by the protection of the informants’ anonymity.

The Experiences of Thai Migrants

Navigating home-like intimacy among female bar workers on TikTok

“…Working in Taiwan, we stay together as a big family … For introverts, you are not suitable for working in Taiwan because we live together in a home of 20-25 people…” (Fang, a textual excerpt from a video)

Drawing on digital ethnography from eight public accounts who constantly posted videos with hashtags pertaining to KTV (an abbreviation of karaoke business in Mandarin-speaking locales), nightclub job, and Taiwan; this vignette underlines how imperative digital uses are to foster companionship extended from physical to virtual spaces. A video underscoring the importance of “family” and “home,” produced by Fang, manifests the dynamics of their social media uses, which I coined as “home-like intimacy.” Brokers and migrants typically reside in the same or nearby compounds. Therefore, they can assist inexperienced newcomers to navigate work nature in KTV akin to Filipino sex worker migrants (Hwang, 2021), while forming a community or “home” during their sojourns. Similar to home in a mundane realm, home-like intimacy’s dynamics are also vertical. Brokers portray themselves as “mothers” by assuming the role of protectors. Migrants are cast as their “daughters” who receive brokers’ care. Therefore, brokers extended their roles beyond a simple intermediary (Soriano, 2021) by being responsible in the household realm, either providing food, cleaning, or nurturing, which are conventionally contemplated as invisible labor of traditional mothers, as indicated in Mild’s video.

“I came to check the girls’ condominium today … There are plenty of foods to eat every day. Checking and cleaning the daughters’ condominium …” (Mild, a verbal excerpt from a video)

The extension of care from actual to virtual spaces emphasizes the reinterpretation of home as it often revolves around familial ties’ care to migrants’ care within the community. An online depiction of care works as verification of physical care that brokers provided to migrants, thereby framing Mild as a good mother, as praised by other migrants in the comment section, who makes her home more enchanting. This care within a “chosen family” not only constructs a sense of unity and proximity due to circulated support but also retaliates against the political economy of undocumented migration, which ushers them into precarious statuses as migrants and bar workers (Ip, 2017; Francisco-Menchavez, 2018; Wallis, 2018). Moreover, such support and positive affect serve as an inducement for prospective migrants to work in Taiwan’s KTV, then join the community, due to the flow of inquiries about migration in the comment section.

LINE as a safe digital space for emotional and informational belonging

For Thai migrant workers in Taiwan, particularly those in construction and manufacturing sectors, LINE supports two primary functions. First, it enables migrants to sustain transnational social roles through video calls and daily chats, reinforcing familial bonds and emotional presence. This resonates with Waldinger and Fitzgerald’s (2004) concept of transnational social fields and Wilding’s (2006) notion of virtual intimacies, in which technology facilitates co-presence across distance. Moreover, Madianou (2012) further argues that ICTs help migrant parents manage accentuated ambivalence, the tension between physical separation and emotional proximity, in ways that reaffirm their identity as caring individuals.

“The safest thing is LINE. If you’re not friends, they can’t see anything. But on Facebook, they can visit your profile, take pictures, and copy things. LINE is different. You need someone’s ID, and you can’t get in if you don’t have it.” (Suk, worker, interview, April 2025)”

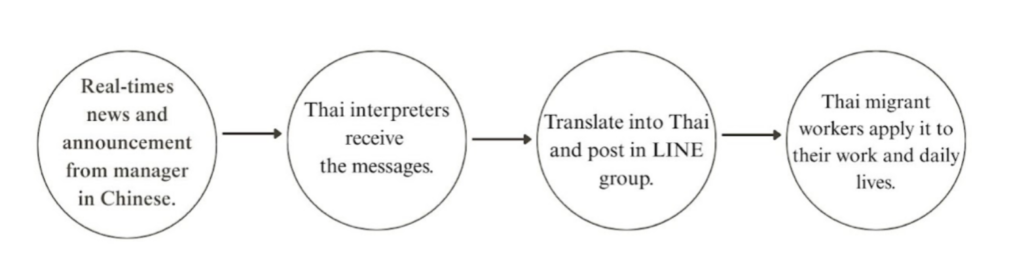

Second, LINE supports informational belonging, as evidenced by Thai interpreters who translate factory updates in real time within group chats (see Figure 1). This is illustrated in the communication simulation diagram between an interpreter and Thai workers in a LINE group. In addition, the Workforce Development Agency under Taiwan’s Ministry of Labor operates a Thai-language LINE account that provides verified news.

“It helps us stay updated with the daily situation in Taiwan… especially the LINE account that provides news in Thai for Thai workers, at least we have information coming directly from the Taiwanese government.” (Kit, worker, interview, January 2025)

These interpreters respond in real time, clarify information into Thai, and provide emotional reassurance during uncertain or urgent moments; their ongoing digital presence and responsiveness on LINE go beyond formal translation duties. This aligns with Fuchs’ (2015) concept of digital labour, communicative work that is often invisible, emotionally taxing, and essential to the functioning of digital infrastructures. The translation work thus becomes more than information transfer; it fosters a sense of informational belonging, where migrants feel included, oriented, and emotionally anchored in unfamiliar environments. As McLuhan’s media theory reminds us (Kaewthep & Chaikhunphon, 2013), technologies like LINE do not simply transmit content; they shape social behavior.

Figure 1. Communication stimulation between interpreters and Thai migrants via Line.

In this context, LINE acts as an infrastructure of care, mediating safety, routine, and proximity amid the uncertainty of precarious labor. These practices, finally, link Wilding’s (2006) concept of virtual intimacy, wherein sustained digital interactions cultivate emotional closeness and relational stability across distance.

The Experiences of Indonesian Migrants

A participatory reflection in Indo Barokah Insani

Indo Barokah Insani, a small Indonesian-owned shop and stall in Zhongli, Taiwan, serves a purpose far beyond mere business. It serves as a vital social, cultural, and digital space for Indonesian migrant workers—especially women—who face precarious working conditions while maintaining connections to their homeland. My experience working part-time there demonstrates how informal spaces like this provide a place for adaptation, mutual support, and subtle forms of resistance to structural marginalization.

Physically unassuming, the shop is bustling with daily life. It serves not only as a place to eat or shop, but also as a community center where customers share stories, chat casually, or make video calls with family back home. Indonesian and various regional dialects, such as Sundanese or Javanese, create a “linguistic sanctuary” that balances feelings of isolation. Bosworth (2022) calls this phenomenon affective infrastructure: a relational space that supports emotional and social life, transcending mere economic functions.

Digitalization plays a crucial role. WhatsApp has become a core application: daily menus are uploaded to Stories every morning, orders come in via text or voice message, and some customers even live-stream meals for their families back home. These activities reflect “ambient co-presence” (Madianou & Miller, 2012), a cross-border presence through technology. Outside the store, apps like TikTok and Facebook share snapshots of work life, promote small businesses, and strengthen emotional and economic networks.

The store also serves as a learning arena. Many workers—formerly factory or domestic workers—practice time management, customer service, and even communicating with Taiwanese despite their limited Mandarin skills. Gestures, translation apps, and the help of bilingual friends are key tools. One coworker said she feels more comfortable here than at her previous job, as she feels more autonomy and dignity. This aligns with Silvey (2006), who emphasized that migrant women seek alternative workspaces to regain control over their lives.

Furthermore, Indo Barokah Insani encourages micro-entrepreneurship. The owner, a former migrant worker, provides a space for others to consign chili sauce, snacks, or crafts. This pattern strengthens economic solidarity and financial independence. Thus, the shop is a “space of resistance” (Lefebvre, 1991), where new social relations are formed outside formal work hierarchies. Indo Barokah Insani shows how migrant communities build meaningful lives through informal, digital, and cultural practices—with creativity, resilience, and solidarity as foundations.

The minority Indonesian: Ethnic Chinese Indonesians and their digital belonging

On one evening, I visited a Chinese Indonesian woman who had opened a small Indonesian shop with an attached cafeteria in the Wenshan District, Taipei. As we were having a conversation, she suddenly received a video call notification on WhatsApp from her husband, who still lives in her hometown in Indonesia. Like many other Indonesians abroad, WhatsApp is the “main staple” of digital media used for daily communication. As she explained to me, she regularly uses WhatsApp to stay in touch with her husband, her youngest son, and her aging parents back home. Living in Taiwan with only three children, she confided that life as a migrant entrepreneur, who spends most of her days in her shop, can often feel isolating. Yet, like many others in her community, she finds digital media to be a lifeline, bridging physical distance and emotional gaps. These platforms enable her to stay connected to her homeland despite the years and miles that separate them. This aligns with what Cabalquinto (2022) argued as hybrid spaces of migrants, where the physical and digital intersect to create a sense of “being at home” while abroad.

My observation also found that digital media could function as a form of social capital that supports migrants’ economic and social survival. As many of my research participants have told me, connections among their Chinese Indonesian communities often help them share opportunities, including transferring business from one to another. The lady, for example, acquired her shop through a connection in her church, which was selling the shop due to their business. In this case, diasporic communities based on ethnic/religious identity, such as the church, have played a central role in shaping networks of support and opportunity. While members may meet in person only once a week for Sunday services, my observation shows that their WhatsApp/LINE groups remain active daily and provide practical assistance.

Another finding from my fieldwork in Kaohsiung, Chinese Indonesians also use WhatsApp groups became central platforms for organizing gatherings, maintaining daily contact, and exchanging personal experiences. Their shared trajectory of marrying Taiwanese spouses has fostered a sense of ethnic solidarity distinct from other Indonesian migrant groups. The use of specific dialects (Hokkien) and culturally specific references within digital spaces reinforces these boundaries, contributing to a more insular but tightly bonded ethnic community. Digital platforms, thus, become a site and serve as a vital form of social capital (Bourdieu, 1986).

Comparative Analysis

Digital media plays a crucial role in shaping the everyday lives of Thai and Indonesian migrant workers in Taiwan. For Thai migrants, particularly undocumented bar workers and brokers, TikTok becomes a site of narrative labor, where affective performances not only validate belonging but also draw others into kin-like networks of trust and support. In contrast, Thai factory and construction workers rely on LINE as a secure tool for labor coordination and emotional maintenance. This mode of bounded co-presence is quieter and more habitual, privileging routine over visibility. The emotional attentiveness and digital availability align with Fuchs’ (2015) concept of digital labour, communicative acts that are essential but often unrecognized in formal job descriptions. These practices generate informational belonging, a sense of being included, informed, and emotionally anchored in unfamiliar contexts.

Among Indonesian migrants, especially women in domestic and informal work, WhatsApp functions as a multi-purpose platform for embedded co-presence. Emotional intimacy is not performed for visibility, but sustained through repetition and shared routines, where co-presence is grounded in mutual participation rather than symbolic hierarchy. For Christian Chinese Indonesians, WhatsApp and LINE serve as platforms for hybrid religious communities, supporting spiritual life through church announcements, prayer coordination, and small-scale commerce. The use of dialect and religious content reinforces ethnic identity and emotional solidarity, demonstrating how digital tools foster both spiritual and material belonging.

While both groups build emotional support through digital means, their cultural logics diverge. Thai migrants alternate between function-specific and expressive platforms, often splitting emotional care from labor coordination. Indonesian migrants embed care into daily communicative practices, weaving together work, faith, and emotion in a more integrated and horizontal manner. In addition, privacy strategies also differ. Thai migrants favor LINE for its discretion and limited access. WhatsApp’s flexibility, by contrast, supports Indonesian migrants’ fluid use across social, religious, and economic domains. Viewed through the lens of polymedia theory (Madianou & Miller, 2012), these choices reflect more than personal preference; they are strategic adaptations shaped by vulnerability, institutional absence, and cultural norms. Moreover, the contrasting use of platforms reveals more than technical preference. It reflects underlying differences in work conditions, cultural values, and migration histories. In conclusion, digital platforms are not just tools, but affective infrastructures that mediate care, coordination, and cultural survival in transnational life.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study examines how digital media shapes identity and belonging among Southeast Asian migrants in Taiwan, focusing on Thai and Indonesian workers. Ethnographic fieldwork reveals that digital media is not merely a communication tool but a vital infrastructure that sustains community, intimacy, and survival in transnational contexts. These practices show migrants as active agents who embed meaning, solidarity, and resistance into digital life, reshaping belonging beyond legal or national categories.

Future research and policy should conceptualize the use of digital media as a core component of migrants’ survival and integration strategies. Host countries should develop contextual and platform-specific digital literacy programs by relevant agencies to empower migrant-managed grassroots initiatives such as micro-entrepreneurship, activism, and community building. Specific platforms may be used, for example, WhatsApp for microbusiness coordination, LINE for secure workplace and advocacy communication, and TikTok for identity expression. Such contextual training would transform digital literacy from mere technical skills into a form of empowerment across economic, social, and cultural dimensions.

References:

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Bauman, Z. (2011). Migration and identities in the globalized world. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 37(4), 425-435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453710396809

Bosworth, K. (2022). What is ‘affective infrastructure’? Dialogues in Human Geography. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221107025

Bourdieu, P. (1986). ‘The forms of capital’, In Richardson, J. G., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood, pp. 241–258.

Cabalquinto, E. C. (2022). (Im)mobile Homes: Family Life at a Distance in the Age of Mobile Media. Oxford University Press.

Chen, K. H. (2010). Asia as method: Toward Deimperialization. Duke University Press.

Francisco-Menchavez, V. (2018). The Labor of Care: Filipina Migrants and Transnational Families in the Digital Age. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.5406/j.ctv6p484

Fuchs, C. (2015). Culture and Economy in the Age of Social Media. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315733517

Hoang, L. A. (2025). Migration Infrastructure, Digital Connectivity and Porous Borders: Vietnamese Migration to Australia. Population, Space and Place, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2868

Hwang, M. C. (2021). Infrastructure of mobility: Navigating borders, cities and markets. Global Networks, 21(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12308

Ip, P. T. T. (2017). Desiring singlehood? Rural migrant women and affective labour in the Shanghai beauty parlour industry. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 18(4), 558–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2017.1387415

Kaewthep, K., & Chaikhunphon, N. (2012). A handbook of new media studies. Senior Research Scholar Project, Office of the Thailand Research Fund.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Blackwell. https://globaldecentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Levitt-Glick-Schiller-Conceptualizing-Simultaneity-A-Transnational-Social-Field-Perspective-on-Society.pdf

Madianou, M. (2012). Migration and the accentuated ambivalence of motherhood: The role of ICTs in Filipino transnational families. Global Networks, 12(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00352.x

Madianou, M., & Miller, D. (2012). Migration and New Media: Transnational Families and Polymedia. Routledge.

Ministry of Labor. (2025). Foreign Workers in Taiwan by Nationality. Ministry of Labor Statistics. https://statdb.mol.gov.tw/html/mon/c12030.htm.

Ong, A. (1999). Flexible citizenship: The cultural logics of transnationality. Duke University Press.

Silvey, R. (2006). Geographies of Gender and Migration: Spatializing Social Difference. The International Migration Review, 40(1), 64-81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27645579

Sobieszczyk, T. (2015). “Good” Sons and “Dutiful” Daughters: A Structural Symbolic Interactionist Analysis of the Migration and Remittance Behaviour of Northern Thai International Migrants. In L. A. Hoang, & B. S. A. Yeoh (Eds), Transnational Labour Migration, Remittances and the Changing Family in Asia. Anthropology, Change and Development Series (pp. 82-110). Palgrave Macmillan.

Soriano, C. R. R. (2021). Digital labour in the Philippines: Emerging forms of brokerage. Media International Australia, 179(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X21993114

Tajaroensuk, D. (2018). A Study of Thai ‘Illegal Workers’ in South Korea [Master’s thesis, Chonnam National University]. https://www.academia.edu/40614319/A_Study_of_Thai_Illegal_Workers_in_South_Korea_Department_of_Non_Governmental_Organization

Waldinger, R., & Fitzgerald, D. (2004). Transnationalism in Question. American Journal of Sociology, 109(5), 1177-1195. https://doi.org/10.1086/381916

Wallis, C. (2018). Domestic Workers and the Affective Dimensions of Communicative Empowerment. Communication, Culture and Critique, 11(2), 213–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcy001

Wilding, R. (2006). ‘Virtual’ intimacies? Families communication across transnational contexts. Global Network, 6(2), 125-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00137.x

Winichakul, T. (1994). Siam mapped: A history of the geo-body of a nation. University of Hawaii Press.

Yang, Y.-H. (2023). Sexuality on the Move: Gay Transnational Mobility Embedded on Racialised Desire for ‘White Asians.’ Gender, Place & Culture, 30(6), 791–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2057446