James Baldwin’s Legacy and Pro-Palestinian Activism in the United States: Reading Mahmoud Khalil’s Letter

Article by Yuan-yang Wang

Abstract:

The conflict between Hamas and Israel has been increasing since Ariel Sharon assumed office as the prime minister in 2001. His tactics of evacuating the Gaza Strip led to many Palestinians being killed. Benjamin Netanyahu and his government have supported more and more policies that not only severely affect the lives of Palestinians but also cost the Israeli Jews their harmony. Anti-Semitism has acutely increased across both European countries and the US since 2019, particularly after the Yellow Vests Movement in France. Yellow vest protesters have organized demonstrations against rising fuel taxes, government policies, and economic disproportions, but some of them targeted Jewish people and their property with malice. Now, the voice of pro-Palestinian activists tells the world that the solidarity of racial groups is of urgent attention. This paper aims to examine Afro-Palestinian solidarity from Baldwin’s legacy by reading Mahmoud Kahlil’s letter and concurrently analyzing the representations of Baldwin in the major exhibitions in the United States. The collision between different rewritings of Baldwin in the visual representations and Kahlil’s letter reflects how Baldwin’s images are installed for various political purposes. The organizers and curators of these exhibitions suggest that it would be politically expedient to rewrite Baldwin’s role as a unifier. Nevertheless, Kahlil inherits Baldwin’s theory about crime, homelessness, and white guilt in his letter.

Keywords: Afro-Palestinian solidarity, homelessness, white guilt, image, rewriter

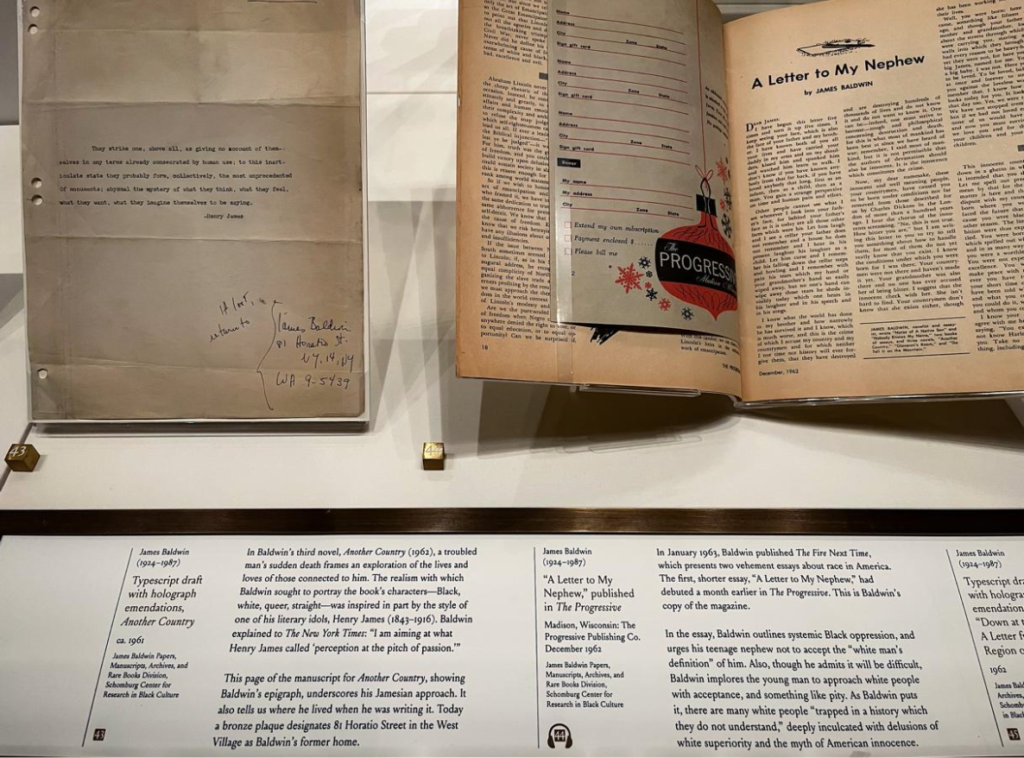

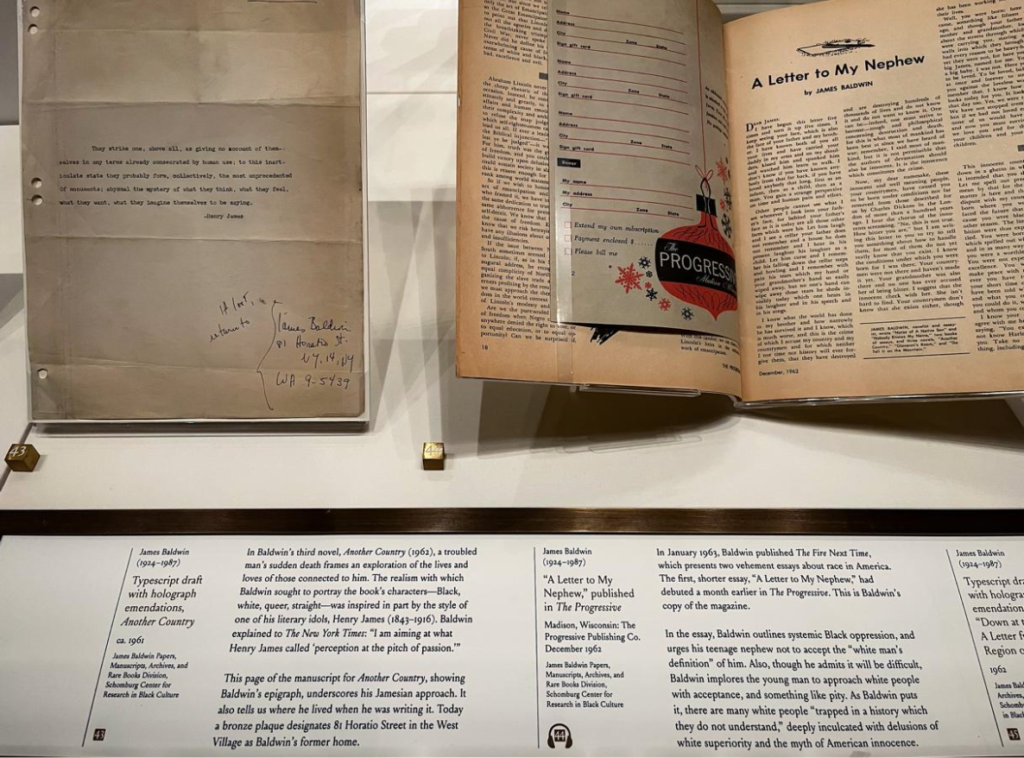

Header image: Baldwin’s typescript draft and “A Letter to My Nephew” published in The Progressive by the author.

Introduction: Crime, Homelessness, and Rewriting Baldwin

In 1961, Israeli officials invited James Baldwin (1924-1987) to visit their country. After his trip to Israel, he completed two crucial works: Another Country in the same year and The Fire Next Time two years later. In The Fire, Baldwin (1993) came up with a theory about crime and Black Power,

Neither civilized reason nor Christian love would cause any of those people to treat you as they presumably wanted to be treated; only the fear of your power to retaliate would cause them to do that, or seem to do it, which was (and is) good enough (p. 21).

White people oppress blacks because they know blacks are influential: empowerment is concomitant with oppression. Also, the mystery of his father forms a central core of his writing theme. Bill V. Mullen (2019) defines this theme with a sense of homelessness,

James Baldwin took his name from the stepfather, but as a child felt the stigma of being an adopted “bastard,” a fact which gave literal dimension to Baldwin’s claim that as the descendants of slaves he was himself a “bastard” of Western modernity built from capitalism and slavery (p. 18).

This sense of homelessness sharpens Baldwin’s perception of multifaceted experiences of dislocation. Baldwin argues that all the minority groups ignite their hatred of each other for the ultimate desire to be American, and seeking a home is a strong incentive for blacks. Identity constructing divides the nation: “[t]he structure of the American commonwealth has trapped both these minorities into attitudes of perpetual hostility” (2012, p. 71). Crime is a double-edged sword: It empowers blacks in pursuit of their home, but it also justifies their wrongdoings. Baldwin’s theory about crime and his theme of homelessness interwove and evolved into a much more sophisticated combination of Black Power and internationalism, especially after he took a trip to Europe and the Middle East.

Literature Review

Many Black studies researchers, including those in African-American literature and film, have been inspired by how representations of socially and globally acclaimed leaders or representatives make a difference in social movements. The author of Baldwin’s biography, Mullen, points out that Baldwin has become “an icon of the global Black Lives Matter movement” (2019, pp. 9-11) because of many rewriters’ rewritings of Baldwin’s work, for example, Peck’s documentary, etc. However, how Baldwin’s images are appropriated in the light of social movement has been underestimated (Craven & Dow, p. 4) and needs further study.

This paper focuses on the relationship between Baldwin as an icon and pro-Palestinian activism in the US. Black Power and pro-Palestinian activism have a lot in common, including their intention to fight against racism and colonialism (Feldman, pp. 62–63). Anti-Semitism could be traced back to Jews as traitors of Christ among European countries (West, pp. 71–73). In the late 1880s, Jews were incriminated by Alexander III for the assassination of the Tsar, and the population of Russian Jews was strictly restricted by law (Schneer pp. 9-11). This policy was extremely inhospitable to the immigrant Jews.

Some Jews came to Jaffa and sought help from the Palestinian farmers to build their homeland. Soon, they regarded Zionism as a way to construct their national identity. The leaders of the Zionist movement, including Theodor Herzl and Chaim Weizmann, struggled to negotiate with different powers to accommodate the immigrant Jews (Schneer pp. 110-128). The British government intervened in purchasing land after the Balfour Declaration was passed in 1917. Hence, Palestinians organized many political movements against the exploitation.

Later, anti-semitism was reconsidered in the US because of the Holocaust in the context of racial slavery (Feldman, p. 70). In the US, Anti-Semitism is regarded as equal to racial discrimination. West (2001) indicates how this analogy is created: “Jews rightly point out that the atrocities of Africa elites on oppressed Africans in Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia are just as bad or worse than those perpetrated on Palestinians by Israeli elites” (p. 74). Jewish Zionists have gradually been taking advantage of the permission to narrate. According to Edward Said (1979), the Israeli supporters as victors have outweighed the pro-Palestinian activists as victims (p. 56-82).

In 1947, the United Nations implemented the Partition Plan. This policy divided the territory of Mandate Palestine into two states and made a distribution respectively to the Jewish state and the Arab state. Nevertheless, there was a lack of consensus between the Jewish Agency and Arab leaders (Pappe, p. 26). One year later, Plan Dalet was formulated to expel more and more Palestinians. The continuing controversies led to the Six Day War in 1967, and this military conflict functioned as a catalyst for fashioning the relationship between Israel and the US.

During the Six Day War, Baldwin wrote two essays: “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They Are Anti-White” for The New York Times and “Anti-Semitism and Black Power” for Freedomways. In the former one, Baldwin (1998) argues, “[t]he root of anti-Semitism among Negroes is, ironically, the relationship of colored people ─ all over the globe ─ to the Christian world” (p. 741). Although Baldwin (2017) revised his statement the following year when he said he was not anti-Semitic in the Dick Cavett Show, he still expressed his concern about fighting for liberty with guns, “[w]hen a black man says exactly the same thing […], he is judged a criminal and treated like one and everything possible is done to make an example of this bad nigger, so there won’t be any more like him” (pp. 81-82). According to Keith P. Feldman, the year 1967 was the turning point of Baldwin’s attitude towards anti-Semitism, “by 1967 Baldwin suggests that anti-Semitism emerged because not only had American Jews become assimilated into a national ideology of exclusion predicated on race ─ but in doing so they had been drawn into a spatially stratified structure of whiteness” (2017, pp. 65– 66).

Recognizing the fact that Israel is exploited and intervened militarily by the US, Baldwin realized that black leftists are likely involved in the white people’s ideology of exclusion, even becoming the culprit of what the newspaper editorial of Haaretz says, “the watchdog” (Selfa, 2002, p. 30). Hence, Baldwin changed his attitude towards the Israeli army. Based on his experiences of developing Black Power, Baldwin shows a potential for Afro-Palestinian solidarity (Seidel, 2016; Alahmed, 2020). His endorsement of Palestine has a significant influence on Afro-Palestinian solidarity, and this needs further research. For example, the “Black for Palestine” statement was signed since the Black Lives Matter Movement has burgeoned globally since 2013 (Mullen, 2019, p. 13). The ramifications of these perspectives provide researchers with a fundamental and succinct prompt to study James Baldwin’s legacy and pro-Palestinian activism in the US.

Methodology

This research is based on André Lefevere’s theory of rewriting, one of the key concepts in his Translating, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame (1992). According to Lefevere (1992), translation is also considered a form of rewriting, including adaptation, criticism, and anthologizing. Examining the German translations of Anne Frank’s diary, he realized that translators not only omitted the parts about sex, but also revised the information about the engagement with the Nazi. Lefevere calls this “the process of ‘construction’ of an image” (1992, p. 59). According to Lefevere (1992), these rewritings impress readers of the target language quite easily compared to what the original texts give to their readers in the source language. This pape considers filmmakers, curators, well-known authors, and pro-Palestinian activists as rewriters.

Reading Mahmoud Kahlil’s Letter with Baldwin’s Legacy

Indicating that Baldwin became much more famous due to the publication of The Fire, David Leeming further describes this upward trend since the 1960s. According to him, Baldwin soon became quite prominent, and “he was recognized everywhere” (1994, p. 219). Francis also points out that, “after The Fire he became a staple of mainstream public media” (2014, p. 7). Additionally, Baldwin has been regarded as a well-known author and a “spokesman,” as Time magazine reprinted Baldwin’s photo on its cover in May 1963 (p. 221). The title of this issue is “Birmingham and Beyond: The Negro’s Push for Equality.” Time established a strong connection between Baldwin’s images and social movements.

Meanwhile, the filmmakers and curators have been highlighting Baldwin’s lyrical and political power. Peck (n.d.) explains that Baldwin is capable of arousing the curiosity of both common readers and academic critics. This exceptional talent is the reason the activists regard Baldwin as an inspired visionary,

When you start to doing it, the Baldwin book, the whole book is underlined, because those are perfect quotes, you know, line after line […] it just hit you on one side and once you think you understood the sentence, and it would hit you with the second part of the sentence and go deeper with you. So, it’s rare that an author can do that to you. (Peck, n.d., 6:48)

Baldwin’s “perfect quotes” are a political manifesto and a poetic prelude. As the editor Alexander Strauss (xxiii) indicates, the documentary is poetic. Intriguingly, many of Baldwin’s quotes are not arranged as a paragraph in a neat format in the transcript of this documentary. Instead, each sentence starts independently as if his quotes are read as poetry. For example, in the section “Selling the Negro,” the layout of Baldwin’s quote is designed like this,

I am speaking as a member of a certain democracy

in a very complex country which insists

on being very narrow-minded.

Simplicity is taken to be a great American virtue

along with sincerity. (Baldwin, 2017)

This quote is narrated after showing the photo of Baldwin and Bob Dylan interacting. Whether or not this interaction was intentional, the photo strengthened Baldwin’s bonds between social movements and literary circles. Moreover, it conveys an implicit message of national unification in the US. The latter, undoubtedly, is consistent with the theme of Baldwin’s address at the University of British Columbia Fall Congregation for receiving his honorary doctoral degree in literature in 1963: “Racism hurts Whites.”

Many curators name their exhibitions after Baldwin’s narratives. Linda Dougherty, the chief curator and senior curator of contemporary art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, and Ekow Eshun curated an exhibition of African diasporic artists with the National Portrait Gallery in the United Kingdom in 2025: “The Time Is Always Now.” According to Linda and Maya (2025), Baldwin’s critical view on desegregation in Nobody Knows My Name was borrowed to call for reconsidering blacks in art history (pp. 2-3). The title is also a quote from Baldwin’s critique of William Faulkner in this book. According to Leeming (1994, pp. 185-86), Baldwin focuses on the paradox of racism despite his decision to return to New York after his self-exile.

Baldwin’s visage has inspired many curators and scholars. For instance, Hilton Als mentioned that Baldwin’s photo was tremendously impressive when he saw the cover of Nobody at the age of fourteen, “[t]he dust jacket of the book featured a photograph of Baldwin wearing a white T-shirt and standing in a pile of rubble in a vacant lot. I had never seen an image of a Black boy like me” (2023, p. 10). Likewise, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. was also inspired by Baldwin’s photo. In the audio guide for “Celebrating 100 Years of James Baldwin” by the NYPL (https://www.nypl.org/spotlight/baldwin100), Gates expresses how Baldwin’s photo illuminated him when he held Notes of a Native Son in his hands, “I was a few pages in before I realized that the face of the Black man on the cover of the book was actually the book’s author! It was at that moment that I first realized that Black people, too, could write books” (the second paragraph of the transcript of Introduction).

However, Als seems to emphasize why Baldwin decided to return to the US deliberately. Als invited artists, writers, and researchers to organize a seminar on Baldwin’s legacy and curated “God Made My Face” in 2019 at David Zwirner Gallery. Al (2023) intends to interpret Nobody as a work of “homecoming.” To him, Baldwin represents the redemption of a Black queer who never abandons his hope to coalesce with his male pioneers and comrades, even though they never recognized him because of his sexual orientation (Al, 2023, pp. 12-13). As a queer black writer, Baldwin’s return to Harlem symbolizes a utopia for black gay people vis-à-vis a heterosexually dominant structure of the Black Power movement.

One year later, Als curated “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon” at the National Portrait Gallery in the Smithsonian Institution. The title is borrowed from Baldwin’s short stories printed in The Atlantic in 1960 and later included in Going to Meet the Man. The protagonist plans to go back to America, but at the same time, he feels anxious about racial tensions happening in his homeland. Rhea L. Combs argues that Baldwin’s narratives and stories are his self-portraits, redeeming the nation as a writer with his social responsibility (2024, p. 7). The curator’s intention in quoting Baldwin is to emphasize his return to America for national unification.

Although Baldwin is not erroneously represented in these exhibitions, I argue that these images don’t straightforwardly point to Baldwin’s theory about crime and homelessness, which accounts for the concept of white guilt, either. White guilt could be traced back to Baldwin’s theory about crime and homelessness, including “Letter to My Nephew” in The Fire, his address at the University of British Columbia, and his 1965 essay “White Man’s Guilt” published in Ebony. Quoting from The Fire as a premonition at the beginning of Race Matters, Cornel West emphasized how white supremacy should be examined through different racial groups and ethnicities (2001, pp. xiii-xiv). Undoubtedly, the Palestinian people should not be an exception. Kevin Lally suggests that white guilt could also be regarded as white shame, “a state of being rather than remorse for a specific action” (2022, pp. 89-90).

In March 2025, Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia University graduate, was arrested by immigrant agents. Later on, he was accused of leading and spreading anti-Semitic rhetoric on the Columbia campus. After Khalil was sent to New Jersey, he was then taken to a detention facility in Louisiana. He sent a letter to the public, “Letter from a Palestinian Political Prisoner in Louisiana.” On the one hand, Khalil discreetly describes how his place was illegally invaded by immigrant agents who did not show a valid warrant. Khalil’s strategy of dispossession echoes with the Black diaspora,

I was born in a Palestinian refugee camp in Syria to a family which has been displaced from their land since the 1948 Nakba. I spent my youth in proximity to yet distant from my homeland. But being Palestinian is an experience that transcends borders. (the sixth paragraph)

On the other hand, he reiterates his pro-Palestinian position to prove this nation’s white guilt, “I have always believed that my duty is not only to liberate myself from the oppressor, but also to liberate my oppressors from their hatred and fear” (the seventh paragraph). Reading Khalil’s letter, one would never be surprised that his strategy parallels what Baldwin addresses to his nephew in The Fire, telling him that white people don’t have an identity because they live as they are told (1993, p. 9). Black Power is the key to this puzzle. Khalil tries to solve it with Baldwin’s legacy.

As Saree Makdisi points out, “[s]upport for the Palestinian struggle is today woven directly into the broader struggle for social justice in the United States, especially among advocates of Indigenous and immigrant rights, police and prison reform or abolition, and Black Lives Matter” (2024, p. xv). In mid-May 2025, the Trump administration claimed that Columbia University had ignored anti-Semitic discrimination disseminated by pro-Palestinian activists and decided to revoke the federal funding. Columbia University has restricted access to its campus to prevent more demonstrations from harming the faculty and students.

Meanwhile, the NYPL has celebrated 100 years of Baldwin with many subsequent events. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture selected many documents from Baldwin for “Celebrating 100 Years of James Baldwin”. There are three items displayed in the bottom right-hand corner, which are supposed to be the end of the viewing from the left side of the exhibition: a typescript draft with holograph emendations of Another Country and “A Letter to My Nephew,” published in The Progressive (later included in The Fire). (fig.2)

Fig. 1 Baldwin’s typescript draft and “A Letter to My Nephew” published in The Progressive by the author.

Baldwin wrote down his address in Harlem on the typescript. By curating this document, the NYPL implies that he always belonged to Harlem. When curators celebrate Baldwin’s legacy and secure his “home” in the public exhibitions, Khalil is likely to be deported and separated from his family in the US by the Trump administration. Many artists and activists have either launched large-scale demonstrations or transformed urban landscapes with their works of street graffiti and visual images. (fig. 3 and 4)

Fig. 3 Street Graffiti in Ironbound in New Jersey by the author.

Fig. 4 A Photo-packed Pillar of a Building in New York City by the author.

Amnesty International (https://www.amnesty.org/en/) emphasizes that Khalil is “a lawful permanent resident in the USA” (the second paragraph of Release Mahmoud Khalil!) and urges people to send messages to Kristi Noem, Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

V. Conclusion

After a decade since Baldwin’s death, his works are still a vast garden from which intellectuals can draw inspiration from and cultivate seeds for literature and social activism. Yu-cheng Lee bought The Fire in Kuala Lumpur and brought it to Taipei, where he studied in Taiwan in the 1970s (Lee, 2007, pp. 3-4). Colm Tóibín read Go Tell It on the Mountain once he was eighteen and still figured out what his Catholic background meant to him as an Irish (Tóibín, 2024, pp. 1-2). In the case of Khalil, Afro-Palestinian solidarity is demonstrated and promoted through Baldwin’s theory about crime and white guilt. Rewriters as representatives of national art institutes should not continue to equivocate Baldwin’s legacy. Otherwise, the tension between anti-Semitism and pro-Palestinian activism would remain a dragon’s teeth in the US.

References:

Alahmed, N. “The shape of the wrath to come”: James Baldwin’s radicalism and the evolution of his thought on Israel. James Baldwin Review, 6, 28-48. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Release Mahmoud Khalil! Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/petition/release-mahmoud-khalil

Als, H. (2023). Introduction: this time. In God made my face (pp. 6-15). The Brooklyn Museum and Dancing Foxes Press.

Baldwin, J. (2012). The Harlem ghetto. In J. Baldwin, Notes of a native son (pp. 59-73). Beacon.

Baldwin, J. (1998). Negroes are anti-Semitic because they are anti-White. In T. Morrison (Ed.), James Baldwin: Collected essays (pp. 739–748). The Library of America.

Baldwin, J. (1993). The fire next time. Vintage International.

Baldwin, J. (2017). [Interview]. In R. Peck (Ed.), I am not your negro (pp. 77-82). Vintage International.

Combs, R. L. (2024). Foreword. In This morning, this evening, so soon: James Baldwin and the voices of queer resistance (pp. 7-10). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, and DelMonico Books.

Craven, A. M. and Dew, W. (2019). Introduction. In Of latitudes unknown: James Baldwin’s radical imagination (pp. 1-14). Bloomsbury Academic.

Dougherty, L., and Brooks, M. (2025, Spring). Exhibition: the time is always now. in L. Napolitano (Ed.), Preview. North Carolina Museum of Art.

Feldman, K. P. (2017). A shadow over Palestine: the imperial life of race in America. University of Minnesota Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/duke/detail.action?docID=2025426

Francis, C. (2014). The critical reception of James Baldwin, 1963-2010. Camden House.

Kelly, R. (1999). “But a local phase of a world problem”: Black history’s global vision, 1883-1950. The Journal of American History, 86(3), 1045-1077.

Khalil, M. and The Guardian. (2025). Letter from a Palestinian political prisoner in Louisiana: dictated over the phone from ICE detention. [PDF]. https://embed.documentcloud.org/documents/25592020-letter-from-a-palestinian-political-prisoner-in-louisiana-march-18-2025/?embed=1

Lally, K. (2022). Whiteness and antiracism: beyond white privilege pedagogy. Teachers College Press.

Lee, Y. (2007). Preface. In Transgression: towards a critical study of African American literature and culture (pp. 3-8). Asian Culture.

Leeming, D. (1994). James Baldwin: a biography. Henry Holt and Company.

Lefevere, A. (1992). Translating, rewriting, and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge.

Makdisi, S. (2024). Foreword. In E. Said, The question of Palestine (pp. xi-xvi). Vintage.

Mullen, B. V. (2019). James Baldwin: Living in fire. Pluto.

New York Public Library and Gates, H. L., Jr. (n.d.). Celebrating 100 years of James Baldwin. New York Public Library. https://guides.bloombergconnects.org/en-US/guide/nyplSchwarzman/item/ae39f198-1c78-4eca-9597-7e693d8b1789

Pappe, I. (2007). The ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Oneworld.

Peck, R. (Director). (2017). I am not your negro. [Film; DVD]. Magnolia Pictures.

Peck, R. (n.d.). Director’s interview with Raoul Peck [Interview]. In R. Peck (Director), I am not your negro. [Film; DVD]. Magnolia Pictures.

Said, E. (1979). The question of Palestine. Vintage.

Schneer, J. (2010). The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Random House.

Seidel, T. (2016). “Occupied territory is occupied territory”: James Baldwin, Palestine and the possibilities of transnational solidarity. Third World Quarterly, 37(9), 1644-1660. 10.1080/01436597.2016.1178063

Selfa, L. (2002). The struggle for Palestine. Haymarket Books.

Strauss, A. (2017). Introduction: editing I am not your negro. In R. Peck, I am not your negro (pp. xxi-xxiii). Vintage International.

Tóibín, C. (2024). On James Baldwin. Brandeis University Press.

West, C. (2001). Preface 2001: democracy matters in race matters. In Race matters (pp. xiii-xix). Vintage.

West, C. (2017). Race matters. Beacon Press.

Zaborowska, M. J. (2025). James Baldwin: The life album. Yale University Press.