On the “Jalan Balik” Exhibition at The George Town Festival 2024: Hug Back the Identity as an Indonesian-Chinese through Art

Article by Muhammad Irfan

Abstract: Paulus Supomo (1955-2021) was not a typical artist. He had no formal art school experience and spent most of his life as a low-wage laborer in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, without significant financial success—until art changed his life at the age of 66. Art not only transformed the course of his life but also reshaped his identity as an Indonesian-Chinese and strengthened his bond with his son, Yulius Iskandar, who is now responsible for preserving his legacy.

This article is written not only as a report on the exhibition at The George Town Festival 2024, but also as a testimony to the complexity of the Chinese-Indonesian community and to how the regimes affected their understanding of their own culture and identity. This exhibition is expected to share how art can be a form of reconciliation.

Keywords: Indonesian-Chinese, visual art, reconciliation, identity, Jalan Balik

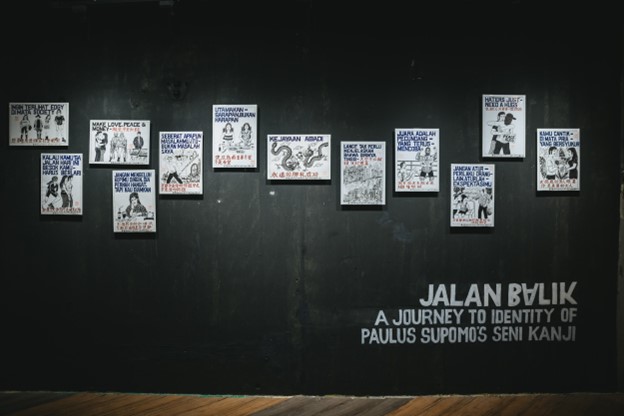

Header Image: Jalan Balik exhibition (Photo by Yew Kok Hong for GTF2024)

Introduction

From July 19th to 28th, Lee Cheah Ni and I curated an exhibition for the Indonesian illustrator Paulus Supomo, famous for his moniker, Senikanji. These works are now managed by Supomo’s son, Yulius Iskandar, who was also the mastermind behind Senikanji’s ideas. Having worked in the entertainment industry, especially in music and pop culture, for more than a decade, Yulius encouraged his father to take his hobby of drawing seriously.

Supomo grew up in the northern coast area of West Java in the 1960s. In his teenage years, he moved to Bandung, the capital city of West Java, to look for a job.

During the early years of Suharto’s New Order regime, being Indonesian-Chinese was not easy. Indonesian-Chinese people were often accused of being communist sympathizers following the 1965 communist massacre in Indonesia; some of their schools were closed; they were required to change their names to more “Indonesian” ones; and they were not allowed to practice their culture, such as celebrating Chinese New Year or learning their language.

Living in this environment, Supomo often hid his identity as an Indonesian-Chinese by tanning his skin or wearing sunglasses. It was difficult for him to find a proper job, especially since he only graduated from elementary school. As a result, he could only work as a low-wage laborer, with a monthly salary that never exceeded USD 150 for most of his career.

However, he had been drawing as a hobby since childhood. According to Yulius, his father rarely spoke to his two sons. Every time he returned from the factory where he worked, he would stay in his room, listen to music, read the newspaper, and draw on scrap paper.

Supomo never took his talent seriously, viewing it only as a hobby, until Yulius promoted his work on social media. It went viral in 2018, and Yulius encouraged his father to believe in his drawing ability and start a new life. At the age of 64, Supomo left his job at a factory and became an artist.

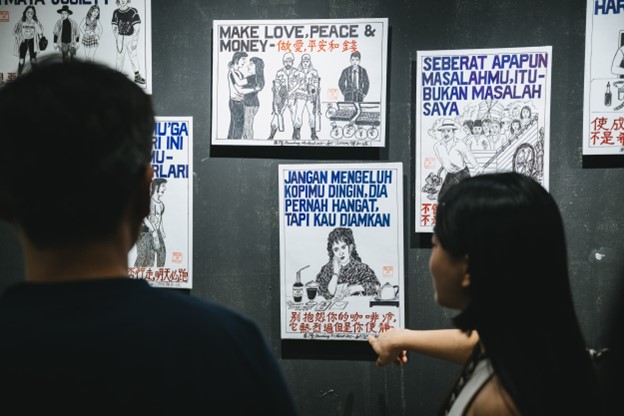

Incorrect Mandarin

Armed with A2 paper, felt tip markers and sometimes silly quotes in Indonesian and Mandarin, he portrayed the casual lives of people in the real world and social media. His distinctive art-style made him famous and he went on to become a big artist who collaborated with a lot of brands and products.

Interestingly, we in Indonesia thought all the quotes in his works were written correctly, including those in Mandarin. However, when I brought these works to Taiwan, some of my Taiwanese friends told me that the Mandarin in Senikanji’s works was understandable but grammatically incorrect or even contained typos. When I learned this, I felt it was a unique characteristic of Senikanji’s work for Mandarin speakers and, on the other hand, a reflection of the experience of Indonesian-Chinese who faced cultural genocide during the 32 years of Suharto’s regime, a fact that people outside Indonesia might not know.

According to Yulius, Supomo learned Mandarin in a five month short-course held by the Church with a Taiwanese teacher in 2007. Through this experience, Supomo found himself again an Indonesian-Chinese.

Even though the course didn’t make him fluent in Mandarin, Supomo tried his best to still keep in touch with it. Reading the dictionary, practicing Mandarin characters in his free time, or visiting nearby tourist destinations just to say ‘ni hao’ and start small conversations with tourists from Mandarin-speaking countries were among his efforts. His aims were also simple: “At least someone in our family can speak Mandarin”.

Given these limitations, it’s not surprising that the Mandarin text in his works sometimes contains mistakes; yet these mistakes became a unique trait in his artwork.

Stereotype as an Indonesian-Chinese

The Indonesian-Chinese have often been stereotyped as wealthy, good at making profits, apolitical, and less committed to national interests (Kuntjara & Hon, 2020). However, Supomo’s family lived in direct contrast to this stereotype.

According to Yulius, his family was very poor. He described his life in the past as “Chinese but poor, living in a very small house and didn’t even have a motorbike”.

Other than that, like the majority of Indonesian-Chinese community, often described as “forming an exclusive ethnic group which is reluctant to mingle with indigenous Indonesians” (Kuntjara & Hon, 2020), Supomo’s family lives together in the Sundanese village on the East-side of Bandung city. Sundanese are a majority tribe living in West Java.

Yulius remembers that living in this situation was a bit hard in his young age. According to him, the locals’ perception of his family as rich clashed with the reality of their financial issues, which estranged them from “typically rich” Indonesian-Chinese families.

Yulius described his family as “minority among a minority”. “We can’t blend in with the Indonesian-Chinese community because we’re poor, but for the locals, they are thinking we are rich because we’re Chinese,” Yulius added.

The difficult situation Yulius faced at that time strained his relationship with his father. Moreover, his father was a cold man that had few topics to talk about with his son. Since junior high school, disappointed Yulius often left home and sought activities outside, eventually becoming active in the underground music scene of Bandung City.

Art as “Jalan Balik”

Cheah Ni and I chose ‘Jalan Balik’ as the title of this exhibition to encapsulate Supomo and Yulius’s journey as a team that built Senikanji from scratch, their collaboration, their struggle to rebuild their relationship as father and son, and their efforts to rediscover their identity as Chinese, which they had long denied.

‘Jalan Balik’ is derived from Malay/Indonesian language, meaning ‘A Way Back Home.’ We view Senikanji’s art as a turning point that not only changed Supomo’s life but also deeply affected his family, including his son Yulius. Although Supomo only became an artist in the last few years of his life, his art had a lasting impact on his entire family.

Yulius recalls that he began to care more for his father after having his first child. He apologized for having distanced himself from Supomo for a long time and wanted to learn how to be the best father he could be by reflecting on his own experience with Supomo. In his effort to rebuild their relationship, Yulius encouraged his father to start drawing again. With his experience in show business, Yulius aimed to promote his father’s talents. Little did they know, this formula would prove successful.

However, like many success stories, the collaboration between Supomo and Yulius wasn’t without challenges. According to Yulius, his father was a stubborn man and a very conservative Christian. To Supomo, some of Yulius’s ideas seemed to go against his beliefs and faith.

For instance, when Yulius asked his father to draw a dragon, Supomo hesitated because he felt that this mythical creature conflicted with his Christian beliefs. Yulius had to persuade his father until Supomo was convinced that it wouldn’t compromise his faith.

Paradoxically, despite his conservative views, Supomo encouraged his son to learn Mandarin, which he saw as ‘preserving ancestral culture’ (Dass, 2023). This was surprising to Yulius, who knew his father as someone who avoided Chinese New Year due to religious reasons, considering it a Confucian ceremony.

As curators, we see art as a bridge that brought Supomo and Yulius back to their roots, allowing them to reconnect as father and son while reclaiming their identity. Art even allowed them to trace their heritage and explore opportunities that Supomo could never have imagined in his lifetime.

“If he knew I could bring his works abroad, he would be happy. I wish he were here,” Yulius said.

References

Kuntjara, E. & Hoon, CY. (2020) Reassessing Chinese Indonesian stereotypes: two decades after Reformasi, South East Asia Research, 28:2, 199-216, DOI: 10.1080/0967828X.2020.1729664

Dass, F. (2023) Senikanji: Berdasarkan wawancara dengan Yulius Iskandar & Supomo, Binatang Press.