![Wired Tianxia, Wounded Borders: Ressentiment, Firewalls, Migrant Bodies, and Aesthetic Interventions [Part I] Wired Tianxia, Wounded Borders: Ressentiment, Firewalls, Migrant Bodies, and Aesthetic Interventions [Part I]](https://cjdproject.web.nycu.edu.tw/wp-content/uploads/sites/167/2025/08/Joyce-1_11zon-1024x576.png)

Wired Tianxia, Wounded Borders: Ressentiment, Firewalls, Migrant Bodies, and Aesthetic Interventions [Part I]

Lectures by Transit Asia Research Network

Abstract: What unfolds when Tianxia— “All-Under-Heaven”—is digitally interwoven into a global Großraum? Can such a wired realm nurture harmony as kin within a planetary household? Unlikely. Ressentiment festers beneath the surface, shaped by geo-historical legacies and geopolitical anxieties. Apparatuses like Germany’s proposed digital Brandmauer or China’s Great Firewall are merely the architectural facades of deeper affective fortifications. These sentiments, displaced onto racialized others, migrants, and outsiders, manifest as localized xenophobia and structural precarity, and echo through contemporary artistic expression. This panel examines these entanglements across Europe and Asia while envisioning ethical and intellectual interventions against the repressive currents of our digital zeitgeist.

Keywords: ressentiment, digital governance, migration, tianxia

The lectures are divided into Part 1 and Part 2. This article, part 1, contains two out of five lectures.

Background

Transit Asia Research Network (TARN) is a research collective dedicated to examining the profound transformations and critical challenges within the complex geopolitical landscape of Asia and the wider world, particularly those related to conflict, inequality, and the enduring legacies of colonial power relations. In 2023, we organised a summer school titled Decolonisation in the 21st Century. Our collaborative research and reflections culminated in a published volume: Decolonisation in the 21st Century: Rethinking Coloniality, Resistance and Solidarity. Five of the authors of this volume are present today at this table.

As part of this programme, after the summer school, we travelled together to the fishing ports in southern Taiwan, where we visited officials from the port bureau, the fishers’ association, and local NGOs. We also engaged in conversations with foreign fishers about their difficult working conditions. Through these shared efforts, we have gradually built a sense of comradeship. Each in our own way, we lean somewhat to the left—committed to addressing the concerns of marginalised populations and unequal citizens, believing in struggles from below, engaged in empirical social research, yet deeply invested in theoretical inquiry. At the same time, we are drawn to artistic sensibilities and critical thought.

This panel addresses the rise of authoritarian regimes in our time, while responding to the theme of this conference—ressentiment. For us, ressentiment takes various forms, locating its scapegoats in racialised, gendered, and marginalised others—both domestically and internationally. As a deep-rooted sense of antagonism and insecurity, it contains neither humour nor irony but instead manifests as stubborn disavowal and brutal suppression. We analyse how these affective undercurrents are not merely episodic but structural, systemic, and institutional, with deep historical roots. Through the artworks, we trace a long history of migration in East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and artistic intersections with Europe. We also consider how intellectual interventions and experimental practices might resist the authoritarian and repressive logic of our age.

[1] Digital Tianxia, Ressentiment, and the Struggle for Alternatives

My talk begins with the concept of Tianxia, all under heaven—or more specifically, Digital Tianxia, New Tianxia—and raises the question: Why does the Chinese Tianxia discourse recur today? Who invokes it, and to what end? What is the psychology and mentality embedded in this discourse? Does it signal a new Nomos of the Earth, a new world order?

Literally translated as “All-Under-Heaven,” Tianxia originated as a moral and political cosmology—a vision of universal harmony under virtuous imperial rule. In traditional Chinese historiography, the emperor was the “Son of Heaven,” his legitimacy granted by the Mandate of Heaven, and his rule claimed to be exercised through benevolence and ritual propriety. Yet Tianxia was never merely an idealistic vision. Historically, it functioned as a mutable logic of domination—a sovereign grammar of world-making, realised through military expansion, ethnic genocide, forced assimilation, tributary rituals and trade, and bureaucratic incorporation. The Qing ruled over a territory more than twenty times larger than the “original” Tianxia attributed to the mythical Yellow Emperor’s domain (c. 2700 BCE). Tianxia’s shifting boundaries trace a topography of cruelty.

As Peter Perdue and other historians (Laura Hostetler, James Millward, and Nicola Di Cosmo) have shown, Qing imperial expansion in the 17th and 18th centuries practised typical settler colonialism, unfolding across Tibet, Xinjiang, Mongolia, and the southwestern frontier. Over centuries, Tianxia operated as an aspiration, a legitimation strategy, and an administrative apparatus—an enduring imperial logic cloaked in the rhetoric of harmony and unity. While many Sinologists emphasised dynastic continuity under one civilisation, they overlooked the fact that the eighty-three dynasties in Chinese history—Han and non-Han alike—each made claims to sovereignty under divine order. Han-ruled regimes (Tang, Song, Ming) and non-Han states (Yuan, Qing), as well as polities led by the Xianbei, Khitan, Jurchen, Tibetan, Tangut, and Turkic peoples, appropriated the Tianxia paradigm of world order-making—that is, a Confucianist hierarchical order of governmentality.

In short, this Tianxia paradigm demonstrates a complex set of coercive and autocratic instruments, including the examination system, institutionalised ethno-political rule and racial classification, administrative bureaucracy, literary inquisitions (wenziyu), ideological surveillance, and military deployment. Dynastic transitions—through conquest, extermination, or incorporation—redefined the territorial contours of Tianxia.

In the 21st century, Tianxia discourse is being revived, not as a nostalgic myth but as a vision and political blueprint for the future. Rebranded as “New Tianxia,” the concept now travels with China’s “peaceful rise,” the Confucius Institutes, and global infrastructural initiatives—especially the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). At the heart of this vision is the Digital Silk Road: a sprawling techno-political project that wires the globe through data flows and cloud infrastructure. As Jonathan Hillman (2021) puts it, it is “China’s quest to wire the world and win the future.”

Chinese philosopher Zhao Tingyang conceptualizes New Tianxia as a world “without exterior” (Tianxia wu wai 天下無外)—a seamless sphere of all-encompassing guardianship. In practice, however, this ideal has become a template for algorithmic and authoritarian control. The wired digital great space now contains various securitized sub-spaces, resembling invisible dome shields fortified by intelligence systems. Domestically, China’s Skynet and Sharp Eyes systems saturate cities and villages with biometric tracking and behavioral analytics. (2 hundred million public CCTVs, in 300 cities)Internationally, Huawei, Hikvision, and Dahua have supplied over 40% of the world’s surveillance infrastructure to enhance national control, and 50 countries have joined the Digital Silk Road initiative.

We must ask: What is the motor of Digital Tianxia? Why is there such a desire to see and to control everything?

We can define the logic of Digital Tianxia—or Tianxia 2.0—as follows: the Tianxia vision provides an expansive space of sovereignty without borders, driven by a desire to see and to control. Unlike classical Tianxia, which relied on ritual submission and territorial absorption, its digital form expands—under bilateral memoranda of understanding—through foreign Special Economic Zones, data hubs, algorithms, fibre-optic cables, and platforms, all enabled by the advancement of digital technologies.

In other words, Digital Tianxia is animated by a drive to monitor, classify, and control All-Under-Heaven through the monopolisation of cyberspace. Beneath this impulse lies anxiety—a fear of losing grip on both the real and symbolic levers of power. That fear feeds a ressentiment born of historical wounds, colonial humiliation, and perceived threats to sovereignty.

Tianxia 2.0 is not about conquering land—it is infrastructural, ambient, planetary. It governs through 5G monopolies, platform hegemony, rare earth extraction, algorithmic sorting, and data surveillance. It silences dissent, pacifies the public, and aestheticises domination.

As revealed in Zhang Jialing’s 2023 documentary Total Trust, these infrastructures are not mere conveniences—they are architectures of domination. Digital Tianxia functions as both a political imaginary and a spatial apparatus. Eva Dou’s recent book The House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company also reveals the deep connection between Huawei’s equipment used to monitor Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang and the hardware from the U.S. company Cisco that enabled China’s Great Firewall.

To name Tianxia 2.0 is not only to critique a particular model of authoritarianism with Chinese characteristics. The critical question is not simply what Tianxia does, but what it enables. It also compels us to interrogate the broader architectures of digital empire—the logics and infrastructures that may be mimicked, adapted, or repurposed by other global powers to suit their own desires.

Resisting it, therefore, requires unmasking its seductive surfaces and exposing the ressentiment pulsing beneath the polished sheen of order and connectivity. It also requires forging solidarities from below—associations of free individuals unbound by state ideology, standing together against infrastructural domination.

What, then, are the possibilities for alternatives in an age where totalizing control masquerades as care?

In response to this tightening regime of networked sovereignty and techno-authoritarianism, we advocate for the cultivation of cross-local, grassroots alliances—situated, tactical, and improvisational. These are not utopias, but grounded actions of refusal enacted through the space of universities.

Consider the role of public forums following online screenings of critical documentaries, offering space for discussions on urgent issues: the surveillance of Palestinians and Muslims under occupation; the education programme Izkor of Israeli youth through patriotic schooling; the conditions of stateless populations like Tibetans and Rohingyas; or the sprawling networks of digital scam economies.

Other initiatives may seem modest, yet their implications are profound: campaigns supporting international fishers’ rights to onboard Wi-Fi—a demand for connectivity not as surveillance, but as autonomy. Collaborative musical projects between migrant laborers and local artists, exhibitions exploring self-publishing and independent zine culture across Wuhan, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Seoul, Hong Kong, and Taipei—these are generative acts of cultural insurgency.

International student-led online journals, peer-to-peer forums, and transnational study groups are already emerging among post-graduate researchers from Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, Nepal, South Africa, Poland, Italy, Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan. These are not just platforms of expression—they are micro-infrastructures of solidarity.

Such acts—cultural, material, pedagogical—are not peripheral to politics. They are politics. They mark the contours of possible worlds yet to be built.

Against the ambient power of Digital Tianxia, we call for persistent, situated resistance. We call for the reinvention of comradeship—not through empire, but through encounter. Not through domination, but through shared refusal. Not at the zenith of the sky, overseeing all under Heaven, but side by side.

[2] Firewalls

There is merit in the proposition that ressentiment is not necessarily something to be overcome. As a feeling that grows in the face of social inequality, ressentiment can provide scope for positive social transformation. However, contemporary political developments complicate this optimistic assessment. We confront a historical moment in which ressentiment and progressive social change operate in tension rather than alignment. The ressentiment of economically and socially marginalized populations—those rendered “surplus” by neoliberal restructuring—increasingly fuels reactionary rather than emancipatory political formations. The resurgence of nativism as a legitimate response to contemporary problems in various countries is just one register of contemporary ressentiment, instantiated also in political discourses of progressive patriotism and left nationalism.

This phenomenon manifests globally, suggesting structural rather than contingent causation. Accordingly, effective resistance must be organised across borders and involve new practices of international solidarity. Thus far the conventional liberal response has been institutional in form and national in scope: the construction of so-called firewalls—procedural and legal mechanisms designed to contain the political expression of popular ressentiment.

The firewall functions as both practice and metaphor. While reactionary politics appears as a spreading conflagration requiring extinguishment, the firewall does not eliminate the underlying combustion. Rather, it establishes boundaries beyond which the political fire of ressentiment cannot advance.

Image: Firewall, Dario Sanna, 2025

Germany’s Brandmauer provides an instructive instance. This post-war covenant among mainstream parties—prohibiting legislative collaboration with far-right political actors—was breached in early 2025 when the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) voted alongside the Alternative für Deutschland on immigration restrictions.

The normative evaluation of such arrangements remains complex. Institutional firewalls may serve legitimate political purposes, yet they simultaneously demarcate the operational boundaries of liberal politics—the threshold at which liberalism’s professed commitment to emancipation and openness transforms into defensive closure. More critically, the firewall’s very existence acknowledges what the US Vice President J.D. Vance (2025) termed at the Munich Security Conference “the threat from within,” thereby revealing the structural complicity between liberal and reactionary formations that such defensive measures seek to obscure.

Today, firewalls are all around us, not only in institutional form but also instantiated in digital infrastructures. Consider the call for a “digital firewall against fascism” by the German hacker group the Chaos Computer Club (2025). Issued in the wake of the CDU’s election win, the proposal advocates technological and legislative measures that would shield German internet users from the kind of “data extraction and analysis” that has purportedly led to a “hostile takeover” in the US.

With emphasis on surveillance regulation, encryption protocols, age verification systems, and digital democracy protections, the call reproduces the defensive bordering logic of the Brandmauer in digital space. This technological iteration, however, reconfigures the geography of threat: rather than emanating from domestic far-right formations, the danger is externalized, attributed to an ascendant “techbroligarchy” in the US.

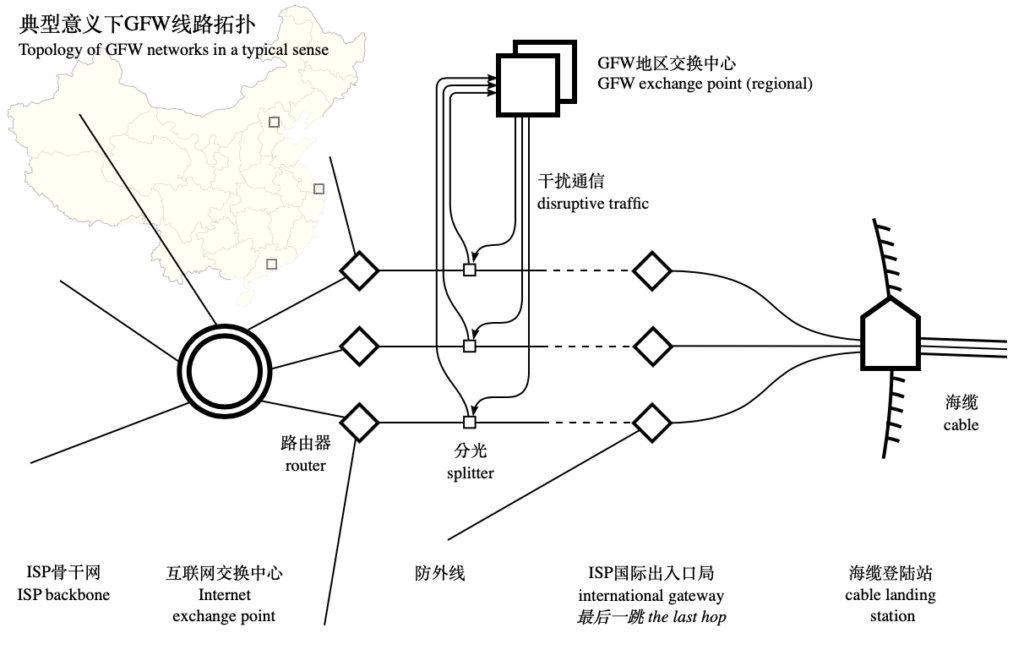

Significantly, the Chaos Computer Club’s call mirrors both rhetorically and technologically what is perhaps the world’s most sophisticated digital content-filtering regime: the People’s Republic of China’s Great Firewall.

Applied selectively and through various means – including IP blocking, packet scanning, and speech and facial recognition – the Great Firewall is the inverse of what Joyce Liu has called digital Tianxia. If the latter is the expression of a “sovereignty without borders” exercised through algorithmic governance, fibre-optic infrastructures, logistical networks and platform capitalism, the former instantiates a rigorous practice of sovereign bordering enabled by analogous digital architectures. We might even go further to say that the technological apparatus of the firewall pushes toward the appearance of another form of bordering and power, not easily reducible to conventional political categories such as sovereignty and governance.

Conventional liberal discourse frames the Great Firewall as an exemplar of digital authoritarianism—a threat to privacy, freedom of expression, and democratic participation. However, this analytical framework quakes when we recognize liberalism’s own deployment of firewalling mechanisms to establish operational boundaries and defend against perceived internal and external threats.

These structural continuities are particularly evident in cases such as the Chaos Computer Club’s advocacy for digital barriers to shield Germany from an emergent reactionary politics in the US—a proposal that replicates the very logic of digital territorialization that liberal critique typically attributes to authoritarian regimes.

Beyond these political paradoxes stemming from the complicity of liberalism and authoritarianism, China’s digital firewall assumes significance within the geopolitical dynamics of the expanding data economy. When reconceptualized as an exercise in data sovereignty and retention, the Great Firewall has generated substantial data accumulation for China.

In contrast to developing economies such as India, which remained open to data extraction by major American technology firms, China has transformed itself into what AI entrepreneur Kai-Fu Lee (2018) calls “the Saudi Arabia of data.” These accumulated data reserves prove particularly crucial for artificial intelligence development at a moment when China faces constraints from American export controls on semiconductor technologies and other strategic items.

This analytical reframing of firewalls offers a distinct perspective on the question of ressentiment. Rather than conceptualizing firewalls as institutional or technological barriers designed to contain the political consequences of ressentiment, this approach situates ressentiment within reconfigured relationships of geopolitics and geoeconomics articulated through digital infrastructures and computational systems.

Central to this analysis would be what Sandro Mezzadra and I call political capitalism (Mezzadra and Neilson 2024)—a concept that among other things captures how capitalist dynamics drive state transformation, shift relations among states, firms and other governance actors, and reconfigure various global divisions and lines, of which firewalls are one manifestation. Unlike discourse on state capitalism, political capitalism reveals continuities in state transformation across regimes typically categorized as authoritarian or democratic, for instance as regards the governance of technological development.

The challenge is to develop an analytical framework capable of accounting for ressentiment’s changing political valence within this context of political capitalism. If ressentiment increasingly fuels reactionary rather than emancipatory politics, this transformation cannot be understood apart from the geopolitical and geoeconomic dynamics that shape contemporary state formation under changing technological conditions.

In this optic, ressentiment becomes entangled with questions of technological sovereignty, data accumulation, and strategic resource control. The defensive firewalls erected against ressentiment’s political expression may themselves serve to consolidate new forms of capitalist territorialization and competitive advantage, even when constructed in the name of liberalism’s most radical longings. Taking stock of these dynamics is crucial if we are to move beyond merely defensive responses toward an understanding of how ressentiment operates within—and potentially against—the logics of contemporary capitalism.

Image: Topology of the Chinese Firewall, Wikimedia Commons, 2012.

References:

Chaos Computer Club (2025) “CCC Demands Digital Infrastructures that are Resilient Against Fascism’s Cravings.” Chaos Computer Club, March 6. Available at: https://www.ccc.de/en/updates/2025/ccc-fordert-digitale-brandmauer (consulted July 2, 2025).

Lee, Kai-Fu (2018) AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order. New York: Harper Collins.

Mezzadra, Sandro and Brett Neilson (2024) The Rest and the West: Capital and Power in a Multipolar World. London: Verso.

Vance, J.D. (2025) “Speech by J.D. Vance,” in B. Franke, ed. Speech by J.D, Vance and Selected Reactions. Hamburg: Mittler. Available at: https://securityconference.org/assets/02_Dokumente/01_Publikationen/2025/Selected_Key_Speeches_Vol._II/MSC_Speeches_2025_Vol2_Ansicht_gek%C3%BCrzt.pdf (consulted July 2, 2025).